What was Belfast like in the early 20th century?

View the photo galleryBelfast in 1911 was enjoying the greatest boom in its history. The chimneys of its linen mills and the cranes which stretched above its shipyards framed the commercial success of the city. This success ensured that Belfast was a place unlike any other in Ireland. Wealth in Dublin and in other Irish cities was usually rooted in trade, in land or in lineage; wealth in Belfast was the product of industry.

By 1911 the city, which sat at the head of Belfast Lough, rolled out into the counties of Down and Antrim. The transformations of a century of industrialisation had entirely redrawn its scale and style. In 1808, only around 25,000 people lived in Belfast; by 1841, this number had increased to 70,000; and by 1911, it had reached 385,000. That was an increase of 10% from the previous census in 1901. It was now, and by a considerable distance, the largest city in Ireland.

This explosion was unique on an island whose population was in persistent decline through the second half of the nineteenth century as a result of famine and emigration. Even the northern industrial towns of England, with which Belfast shared so many similarities, could not match a city which became the fastest growing urban area in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

What made this transformation all the more stunning was that the history of Belfast was a relatively recent one. It had been the site of a medieval castle, but it only really gained any significance at the start of the seventeenth century. In 1603, Arthur Chichester, the son of a Devon landowner who fought in Ireland during the Nine Years War, and who became Lord Deputy of Ireland, was granted Belfast Castle and its surrounding lands.

Chichester laid out a town and settled it with English and Scots. The Catholic Irish lived mainly to the west of the fortified town, which developed slowly as a commercial centre through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Throughout this period it was a relatively unimportant, largely Presbyterian town, which had a reputation for a radical and democratic outlook. This was emphasised by the central part played by Belfast Presbyterians in the emergence of the United Irishmen and their abortive insurrection of 1798.

By then, Belfast was already embarking on the process of industrialisation which so altered its nature. Linen mills and shipbuilding were its most significant economic activities. Capital investment in technology, notably in mechanised spinning wheels, saw Belfast become the leading centre of linen production in the world. The linen mills were based mainly on the Antrim side, where they helped stimulate the development of other industries such as chemical manufacture. By the start of the twentieth century, more than 35,000 people worked in textiles in Belfast.

© Ulster Museum 2008 Y3255: A woman attends to a plain linen loom at Brookfield Linen Company’s mill on the Crumlin Road, May 1911

Photograph reproduced courtesy the Trustees of National Museums Northern Ireland

The iconic Belfast industry, however, was shipbuilding. It did not employ as many workers as the linen industry, but its achievements brought international renown to the city. Throughout the nineteenth century the shallow waters of the city were redeveloped into a major port, which were home to what became the largest ship-builders in the world. In 1859 Edward Harland bought the shipyard in the port which he had previously managed. Two years later he took Gustav Wolff as his partner. They expanded over the following decades, and by 1900 Harland and Wolff employed 9,000 people. In 1911 they launched the Titanic, then the largest ship in the world, which sank so dramatically on its maiden voyage.

© Ulster Museum 2008 H1561: Titanic in the final stages of construction, May 1911

Photograph reproduced courtesy the Trustees of National Museums Northern Ireland

It was these and a whole host of other industries – engineering, rope-making, distilling, tobacco and many more – which forged an extraordinary expansion. The people who flowed into Belfast in great waves throughout the nineteenth century turned a town into a city. The boundaries were extended on several occasions until, in 1888, Belfast was formally incorporated as a city.

The people of the city were divided by religion. Even before the change driven by nineteenth century industrialisation, tensions existed between Presbyterians and Church of Ireland members. The influx of tens of thousands of Catholics brought another new dynamic to Belfast. In 1784 Catholics had constituted just 8% of the population of Belfast; by 1911 that figure had risen to 24%. By contrast 34% of the population was Presbyterian, 30% was Church of Ireland and 7% was Methodist.

Like every significant city in the industrialised world, Belfast streets were a mix of rich and poor. The rich lived in areas around the Malone Road, Botanic Avenue and other salubrious locations. In the narrow streets of working-class areas, particularly around the shipyards, packed red-bricked houses were filled with large families. Social life in Belfast was markedly similar to that in the northern industrial towns of England. Along these streets, working class culture often revolved around a love of sport and music and drink. Within these shared interests, the acute sectarian divide gave the culture of Belfast its own peculiar hue.

.jpg)

© Ulster Museum 2008 WAG 3820 (72): Sandy Row, the heart of Protestant working-class Belfast, ca. 1910

Photograph reproduced courtesy the Trustees of National Museums Northern Ireland

The traditional divides of rural Ulster were recast in an urban context. The nineteenth century saw periodic upheavals with riotous conflicts between Catholics and Protestants. In the early decades of the century there were battles around 12 July parades and around polling days. By the 1850s the riots were becoming unmanageable, often running for several days through the main working-class neighbourhoods of the city.

Recurring riots led newcomers to Belfast to seek safety in numbers. Catholics dominated the south-western part of the city with Protestants dominating much of the rest. This residential segregation reinforced divides which did not ease with the passage of time. Divisions in places of employment – Catholics were grossly under-represented in skilled industrial work, for instance – and the development of separate streams of education confirmed the partitioned nature of the city.

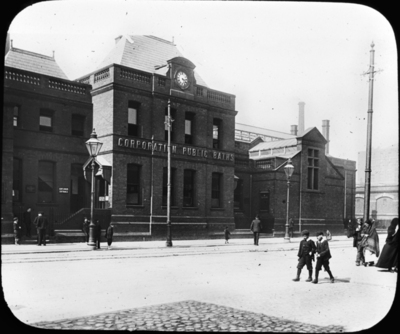

© Ulster Museum 2008 Y8518: Falls Road public baths and free library, in Catholic working-class Belfast, ca. 1910

Photograph reproduced courtesy the Trustees of National Museums Northern Ireland

The politics of Belfast predictably divided upon religious lines. Protestants identified with unionism and Catholics with nationalism. By 1911, with talk of Home Rule for Ireland once again on the increase, the political divide in the city was about to become even more stark. Dublin Castle may have been the centre of the British government’s administration of Ireland, but Belfast was the focal point for loyalism. In September 1911, the unionist leader, Sir Edward Carson, told an Orange Order meeting at Craigavon House: ‘We must be prepared … the morning Home Rule passes, ourselves to become responsible for the government of the Protestant province of Ulster.’ Within a decade, Belfast was the centre of that ‘Protestant province’.

Edward Carson signing Ulster League and Covenant, 1912 . To see signatories to the Covenant, see http://www.proni.gov.uk/index/search_the_archives/ulster_covenant.htm