Sporting, social and cultural life in Belfast in the early 20th century

View the photo gallerySocial and cultural life in Belfast was as diverse as might be expected in any city of its size. With more than 350,000 inhabitants by 1911, the hours which people passed between working and sleeping involved an extraordinary range of activities.

© Ulster Museum 2008 Y10008: Cassie O’Neill of Glenarm dances at the Feis in 1904

Photograph reproduced courtesy the Trustees of National Museums Northern Ireland

The way Sunday was spent in the city was a case in point. Sabbatarianism was a particular feature of the lives of ‘respectable’ people in Belfast, for whom the day revolved around attending religious service and organising Sunday School for their children. For others, Sunday was simply another day to drink. The growing temperance movement in the city could not disguise the fact public drunkenness was a habitual feature of Belfast streets. Pubs were the focal point of working-class communities seeking refuge in cheap whiskey.

The most famous pub in the city became the Crown bar, but there were many more on every street and in every suburb. In fact, it was estimated that in the early 1900s, Belfast held one pub for every 328 inhabitants (see McGlade’s spirit grocery at Cromac St.), though there was also an Irish Temperance League coffee stand on Cromac Street. The scale of alcohol consumption in Belfast led one local clergyman to note that Belfast was a city ‘soaked in liquor’.

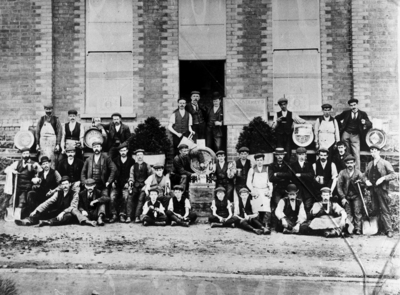

© Ulster Museum 2008 10/01/2;The staff of Caffrey’s Brewery, pictured on the opening of new premises at Anderstown, south-west Belfast (now the Glen Rd.), in 1905.

Photograph reproduced courtesy the Trustees of National Museums Northern Ireland

In a city which was soaked in acute religious and political divides, it was unsurprising that a multiplicity of social and cultural activities (see Gentlemen’s club at Castle Place) not only flourished, but were coloured by peculiar local conditions. Sport was a prime example of this. The professional soccer leagues of northern England were replicated in the working class culture of Belfast: thousands of men in flat caps poured into soccer grounds on Saturday afternoons to attend matches. Many outstanding players came from the city, including the famous Liverpool goalkeeper, Elisha Scott. By 1911 there were five professional soccer teams in Belfast, and they drew crowds of 10,000 on a regular basis. Both Protestants and Catholics had their own teams to support and contests between rival clubs were hotly-disputed, occasionally descending into violence and rioting.

In Catholic areas, the Gaelic Athletic Association had also established a presence which saw hurling matches played in a small number of clubs. The GAA had been founded in 1884 and Michael Cusack, the founder of that association, had repeatedly made it a priority to establish clubs across Ulster. Cusack’s personal desires were not followed through by the association, and the GAA took a long time to establish itself in Ulster. In the early years of the twentieth century, renewed endeavour by men such as Bulmer Hobson to establish hurling leagues in the city, was making progress.

© Ulster Museum 2008 Y4171: Tennis match in progress on courts laid out at the front of QUB, May 1914

Photograph reproduced courtesy the Trustees of National Museums Northern Ireland

Other sports, particularly ones related to a more sedate life in the suburbs also thrived. There were clubs for rugby and cricket and tennis and many other sports which were the product of the Victorian sporting revolution. Fortwilliam Golf Club was well-established. The North of Ireland Cricket and Football Club had been founded in 1868 and six of its members were on the Irish team that lost to England at the first ever rugby international, played at the Oval ground in London in 1875. These included E. McIlwaine, Robert Walkington and Abram Combe. Along the river, there were boat clubs, including the Belfast Boat Club at Stranmillis.

Leisure, of course, extended far beyond competitive sport. By the outbreak of the World War I, there were 15 cinemas in Belfast. The Kelvin Picture Palace – so-called as its site was the birthplace of the famous scientist, Lord Kelvin – on College Square East admitted cinema-goers at ‘popular prices’ of between 3d and 6d. There were daily matinee shows as well as twice-nightly shows at 7pm and 9pm. The city was pocked with tobacconists and with Italian ice-parlours and fish and chip shops and which had started to establish themselves in the early 1900s. There were tea-rooms such as The Dub on Malone Gardens., and many people employed in selling tea and confectionery.

© Ulster Museum 2008 H10-21-825: The tea bar in Carrick House, Lwr Regent Street, c. 1907. It was opened by City Council in 1902, this bar served only non-alcoholic drinks.

Photograph reproduced courtesy the Trustees of National Museums Northern Ireland

Overall, there was a vibrant, complex cultural life in Belfast. Much as in Dublin the shows so associated with English music halls thrived in the city, firstly at the Alhambra and then at the Olympia Palace. The town’s first theatre was opened in the 1730s and, in 1911, plays (and other entertainments) were performed by touring companies at the Grand Opera House (see American singers in town ). The painter, William Conor, was born in Belfast in 1881. He began his career as a poster designer, before going on to become an official war artist during World War I. Poets such as Samuel K. Cowan wrote of life in the city and beyond. Cowan published books of poetry for 40 years, writing on such matters as the Titanic, the opening of City Hall and the second home rule bill.

© Ulster Museum 2008 HB47: The audience at the Grand Opera House watch a performance of ‘A Royal Divorce’ , Saturday 4 August 1917

Photograph reproduced courtesy the Trustees of National Museums Northern Ireland

The late 1890s and early 1900s saw a revival of matters relating to Gaelic culture. Alice Milligan, a Tyrone-born, Methodist College-educated woman started a republican monthly, The Shan Van Vocht, with her friend Anne Johnstone. Others, such as Francis Joseph Biggar, a member of the Royal Irish Academy, also supported of the Irish language revival. Others who were active in the cultural life of the city were writers such as Joseph Campbell, F. Frankford Moore, Samuel Keightley, Mrs. Margaret Pender and Forrest Reid.

In an attempt to improve the health of the people, as well as to provide leisure opportunities, there were public baths, such as the Ormeau Public baths which were built in the 1880s. Within the city there were parks laid out such as Ormeau Park and the Botanic Gardens. In fact, it was to the Botanic Gardens that the first tram (initially horse drawn, but electric from 1905) route in the city was established, linking it with Castle Place in 1872. The establishment of a network of trams and an extended railway system linking Belfast with surrounding areas and beyond changed the social opportunities of the people of the city.

The first trains left Belfast in 1839, connecting the city with Lisburn. The Ulster Railway expanding steadily throughout the rest of the century, with the Great Victoria Street Station as its hub. In the hinterland of Belfast, along the coastal towns of Antrim ( see master mariner in Ballycastle) and Down, there were regattas through the summer months. That coast was the focal point for the growth of local tourism and leisure outings. There were hotels and tea-rooms to cater for the people who were drawn from the city out to the sea (see boarding house in Ballycastle). Further up the coast, the Giant’s Causeway was a unique attraction for locals and visitors alike.