Economy and society in Cork in the early 20th century

View the photo galleryCork city’s growth in the eighteenth century was based on the growth of trade into the city and the strength of the city’s butter market and textile trade in particular. By the end of that century 50% of all Irish butter exports came from Cork. The figure for beef was even higher. That trade went into decline after the conclusion of the Napoleonic wars, and the fall in prices that followed. In an attempt to revive the city’s fortunes in the aftermath of the Great Famine, an international exhibition was held in Cork in 1852.

A photograph of the former Cork Butter Market at a time when it housed O'Gorman's hat factory. The firm of T. O'Gorman occupied the building from 1940 until it was destroyed by fire in 1976

(http://www.corkpastandpresent.ie)

A similar attempt was made again with the Cork International Exhibition in 1902-1903. The main site for the exhibition was a park on the western side of the city. The industrial and agricultural exhibits were on a site that is now the U.C.C. sports ground, bounded on one side by the River Lee, and on the other side by the railway and tramway system. There was an industrial hall, a machinery hall, an art gallery, a Canadian pavilion, and various agricultural exhibits and stands. The amusement park at the exhibition contained a skating rink, a shooting gallery and an aquarium.

Cork International Exhibtion 1902: the fish ponds

(http://www.corkcity.ie/ourservices/recreationamenityculture/museum/exhibitionsatcorkpublicmuseum2005/mainbody,3345,en.html)

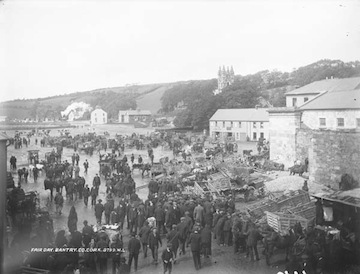

That agriculture was a mainstay of the exhibition reflected the reality of the economy in Cork. In the areas outside of Cork city, agriculture was the predominant employer of men. Of the 100,181 men defined as having a ‘specified occupation’ 58,411 were designated as being of the ‘agricultural class’. There were still thousands of agricultural labourers (see return for Denis Doody of Queenstown, with five agricultural labourers in the household, but just as in the rest of rural Ireland, this class was dwindling steadily towards extinction. There were people working as market gardeners (see William O’Brien of Blackrock) but it was farmers (see John Love, near Schull) who dominated life in much of rural Cork, as only 30,358 men are designated as being of the industrial class.

In towns across Cork, there were, however, drapers (see Joseph Barry in Kinsale), bootmakers (see Seoirse de Bulman in Fermoy) and other tradesmen. Attempts to overcome more than a century of flooding in Douglas had led to drainage schemes on the Tramore and Trabeg rivers. This was led by a group of local people, including a solicitor, Augustus Graham Goold, with a retired army officer William Newenham as its chairman.

The census recorded that the industrial class of 12,609 made up more than half of the 22,420 men with a specified occupation in Cork city (see boarding house on Wandesford Street in Cork city full of shoemakers, brewery workers, clerks, egg packers, labourers, tailors and tram conductors) The industrial class was also the highest employer of women with 4,636 of the 10,018 women with specified occupations employed in industry. There were also governesses (see Gladys Williams at Corbally) and nurses (see Isabel MacBeath at Queenstown). For women in the countryside domestic service was by far the most usual occupation of women with a specified occupation, accounting for 11,681 of their number.

The apparatus of government provided significant employment in Cork. There were local government employees (see Auditor John More O’Ferrall at Shrewsbury Villas in Cork city) and magistrates (see Matthew Ambrose at Queenstown). There was a significant army presence. Members of the British Army were stationed at Haulbowline in Queenstown and others were stationed on Spike Island. There were also soldiers (see Marriot Benson in Cork city) and reservists (see Captain De Berry in Ballyhay) living all across the county.

Members of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers take a rest in a field in Fermoy, Co. Cork c. 1900

(NLI, LCAB 04046)

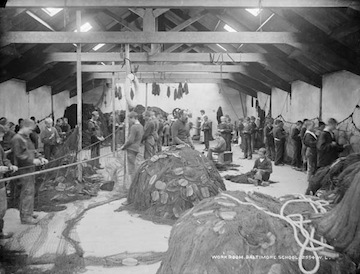

The sea offered various and important forms of employment (see marine engineer William Barker at Queenstown) to the people of Cork. All along the coast, people lived on ships (see Michael Halley at Dungarvan). There were men who worked for the coast guard (see Richard Tucker at Rockisland) and there was an important mackerel industry in Baltimore (see return for Industrial School), though this was in decline by 1911. The rejuvenation of the industry from the 1870s had helped develop the local economy, including the establishment of a Fishery School in 1887, which by 1891 had a total of 162 people in residence: 10 staff and 152 boys.

Boys at work making nets in the workrooms of the Baltimore Fisheries School (Industrial School) ca. 1900

(NLI, LROY 02594)

The port at Queenstown (renamed Cobh in 1922) was central to the process of emigration to America between the Great Famine and 1950, but this was just one of its functions. Queenstown (see shipbuilder Oliver Piper) became renowned as the last berthing place of the Titanic which sunk in the year after the 1911 census on its maiden voyage to New York. One of the travellers who survived the sinking of the Titanic was Nora O'Leary of Annahala, near Macroom, an 18-year-old farmer’s daughter. She was on her way to live with her sister, Katie O’Leary in New York. Later, on a holiday home to Ireland, she met and married Tom O’Herlihy and they lived at Ballydesmond.

Queenstown was to be dramatically changed during the Great War by the influx of thousands of British and American navy (see Royal Navy ship’s crew at Haulbowline) personnel who built hangars and even skating rinks in the town. Friendship between the man in charge of the naval base at Queenstown, Admiral Lewis Bayly, and the Bishop of Cloyne, Robert Browne facilitated the delivery of a 42-bell carillon from Liverpool for the new cathedral. There was tragedy, too, when the wheels of makeshift hearses rattled across the streets of Cobh, carrying the bodies of the drowned who had been on board the Lusitania. The Lusitania was sunk by torpedoes fired from a German submarine on 7 May 1915 when sailing from New York to Queenstown. Many of those on board were returning Irish emigrants. Fishermen from Kinsale and surrounding areas pulled some survivors from the water, but 1198 people were lost. A monument was subsequently erected in Casement Square as a memorial.

People line the harbour wall to catch a view of a bunting-clad Naval ship in Queentstown

(NLI, LROY 02700)

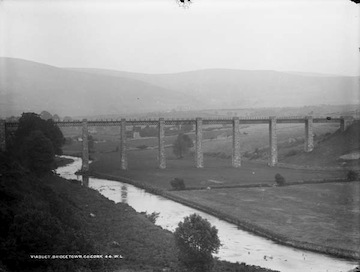

Cork had a burgeoning tourism industry. The city and the coastline had many prominent hotels, including Keenan’s and the Marine Hotel in Glandore in West Cork. Rail transport was vital to the development of tourism. Train lines ran from five Cork stations. The largest station was the Great Southern and Western Station on the Lower Glanmire Road, which ran lines to Dublin, Queenstown, Killarney, Waterford and Rosslare. There were also stations at Albert Quay, Albert Street and Capwell covering routes to Bandon, Glengariff and Macroom. The Western Road Station was on a small island where the River Lee forked in two, and it housed local trains for Coachford, Blarney and other areas. There were also tramways (see tramway labourer Wlliam Hayes) in the city, running to Douglas, Ballintemple, Blackrock and Sunday’s Well.