What was Cork like in the early 20th century?

View the photo galleryIn his memorable essay Cork: anatomy and essence, the Cork historian, Prof. John A. Murphy, notes that enthusiastic Corkonians accept as a richly-deserved compliment the idea that Cork has some claim to be regarded as a microcosm of the entire country. He concludes that the sturdily independent attitude of mind in Cork “is the essence, in the eyes of Cork people at least, of the most distinctive county personality in Ireland.” This notion manifests itself in the image of ‘Rebel Cork’, of the ‘Independent Republic of Cork’, and of Cork as the true capital of Ireland.

The rebel county? This photograph shows crowds watching the procession of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra on the north side of the South Mall in 1903.

(http://www.corkpastandpresent.ie)

In part, this is a reflection of the size of the county. Cork in 1911 was the largest county in Ireland, with a population of 392,104. The size of the county was such that even though Cork was the largest city in the south of Ireland, it did not dominate Cork in the same way that Dublin city dominated Dublin. It was also an extraordinarily diverse county: Catholic, but with a significant Protestant presence; rich in the quality of its agricultural land, but with a rugged landscape in the west of the county; and wealthy in parts, but with a large relatively impoverished majority. Indeed, there was much about Cork in 1911 which suggested disunity, rather than unity.

A Catholic county: a group of men and boys pray at the Cork city tomb of Father Matthew, the 19th century temperance reformer, ca. 1900

(NLI: LROY 02687)

If the size of Cork shaped the identity of the county, so did its politics. Cork was divided in 1911 between a small but powerful unionist community, a broadly nationalist majority, and a small number of radical republicans. The city which extended fulsome welcome to visiting monarchs from England – not least Edward VII when he came to the city in 1903 – and which was home to important forces from the British army and navy, was also home to radicals who sought to sunder the union which bound Ireland to Britain. Within little more than a decade the status quo had been turned on its head and republicans from the county – including Michael Collins and J.J. Walsh – were part of a new government charged with running an Irish Free State. It was a representation which reflected the place of Cork in securing limited independence for Ireland.

No change of government could mask the significant social and economic challenges which faced the state. This was as true for Cork as it was for any other county in Ireland. The greatest indicator of this was the impact of economic stagnation on the population of the county. Indeed, the story of Cork in the second half of the nineteenth century and in the first decade of the twentieth century is, in many respects, the story of Irish emigration. It was from the port of Queenstown (renamed Cobh in 1922) in Cork that many Irish emigrants left for the United States. In the 100 years before 1950 around 2.5 million of the 6 million Irish people who emigrated to America did so through that port. A staggering number of these people were from the county of Cork. Between the end of the Great Famine of the 1840s and the 1911 census around 550,000 Cork people emigrated in search of a living.

H.M.S. Howe naval ship enters Queenstown, Co. Cork. The port of Queenstown was the point of departure for many Irish emigrants to the United States from the late 19th century through to 1911.

(NLI: LROY 06338 )

The decade before the 1911 census recorded the continuation of this process with 43,593 Cork people emigrating, although this was the lowest number to emigrate in any decade after the famine. It compared with the high of 148,009 people emigrating in the decade between 1852 and 1861. Despite the improvement the Cork Board of Poor Law Guardians was continuing to apply for grant aid from the government to subvent emigration. Population change did not hit rural and urban areas in equal measure. In some rural areas the population decline continued to be precipitate; in Skull it climbed above 15%. The urban areas told a different tale. The small towns of Youghal and Fermoy grew by 4.7% and 12%, respectively, and Cork city ended the decade as a marginally more populous place, with its number of inhabitants 0.7% higher. This left the population of the city at 76,673. Even this improvement, however, represented a decline from the 80,000 or so inhabitants of the city as far back as 1821 and again in the 1880s.

Sun-seekers on the Esplanade in Youghal, C. Cork. The population of this town grew by 4.7% in the decade before 1911.

(NLI: LROY 11479)

Employment in the city of Cork came in the same guises as in many other cities in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The breweries of Murphy’s and Beamish and Crawford, as well as the distilleries, tanneries, foundries and mills gave much-needed work. Those who lived and worked in Cork county depended, for the most part, on agriculture and on the sea for their livelihoods. In the countryside this was a world of tenant farmers and agricultural labourers. Along the coast fishing and related industries were vital. At Youghal, Kinsale, Castletown and Bearhaven there were important fishing bases.

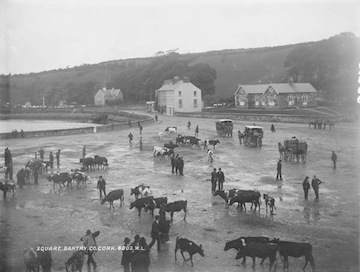

Cattle fill the square in Bantry, Co. Cork. Outside of Cork city, agriculture was the mainstay of the economy and the largest employer.

(NLI: LROY 08802)

Possibly the best known place in the county was Queenstown, the port town of nearly 8,000 people, which later – in 1922 – was renamed as Cobh. It was from Queenstown that so many Irish emigrants sailed to America in search for a better life in the decades between the end of the Great Famine and the inauguration of transatlantic flights. In 1912 Queenstown earned dubious renown as the last berthing place of the Titanic, which sank on its maiden voyage to New York. Quite a number of Cork people who filled out the 1911 census were aboard the Titanic when it struck an iceberg; several of those – including Nora O’Leary and Dannie Buckley – survived to tell the tale.