Education

View the photo galleryFree primary education after 1831, and the enforcement of compulsory education for children between the ages of 6 and 14 in 1892 ensured that all the children of Dublin had access to a basic level of education, at least in theory. The reality was that the poverty of working class Dublin ensured that the majority of its children left full-time education before finishing national school. With many children forced to contribute to the upkeep of their families by selling wares or begging on the streets, the poorest children often gained only a patchy education.

The poverty of working class Dublin ensured that many children left full-time education before finishing national school

(RSAI, Darkest Dublin, 94)

The result was that in schools such as Synge Street Christian Brothers’ school, the numbers dwindled significantly as the classes got older. Crucially, however, the national schools (see return for teacher Collins of Cabinteely) did promote basic literacy, for most though by no means all who lived in Dublin (see return for Deering of James's Terrace, who could not read or write). Away from the national school system a range of different private schools prospered across the (see return for German High School at Wellington Place, Donnybrook). Some were grind schools dedicated to preparing students for the civil service examinations.

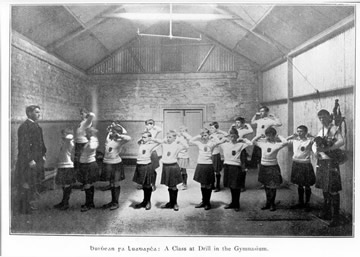

By contrast, Patrick Pearse founded St Enda’s school in 1909 in opposition to the examination-orientated ‘murder-machine’ of the state system (see return for Seymour, retired Secretary of National Board of Education, Simmonscourt), and designed a curriculum intended to promote a rounded awareness of Gaelic culture and history.

In Clontarf, the Hibernian Marine School catered for day-students and 60 boarders and was initially established for boys from seafaring families who were orphans, or from families unable to afford fees. Also on the northside, in nearby Artane, hundreds of children lived at the Artane Industrial School where they were under the supervision of Christian Brothers. Similar industrial schools operated in various parts of the city including St. Anne’s on Booterstown Avenue and the various O’Brien’s Industrial Schools, like this one on the Malahide Rd.

Attempts to provide non-denominational secondary education, such as they were, were opposed by the churches. Secondary schools in Dublin were privately run, divided by religion and, apart from Christian Brothers’ schools (see reference to school at Merville Terrace, Clontarf), were fee-paying. As well as the fees from students, the schools were funded by the state on the basis of the results achieved in examinations. There was a range of prestigious fee-paying schools in Dublin run by the Catholic religious orders, including Blackrock, and Castleknock colleges. Their students were drawn from the Catholic middle classes and destined for a career in the professions, or in the public service across the British empire. Equally prestigious schools were run for Protestant boys, including Monkstown Park.

Castleknock College, one of the City's most prestigious private Catholic schools c.1900.

(NLI, LROY 1120)

There was a growing number of secondary schools for girls in the city, including the Dominican College for Catholic Girls on Eccles St. Alexandra College, on Earlsfort Terrace, pioneered the education of Protestant girls and sent an increasing number of its pupils on to university. Wesley College educated Methodist boys in Dublin and, in September 1911, it opened its doors to girls who desired “to secure such training as will fit them for professional and business careers”. The college purchased 110 St. Stephen's Green as a girls’ hostel. It had formerly been known as The Epworth Club, a boarding house for young Epworth business men coming to Dublin, which had ceased to serve its purpose. Six boarder girls and fifteen day-girls joined the 175 boys already in the college.

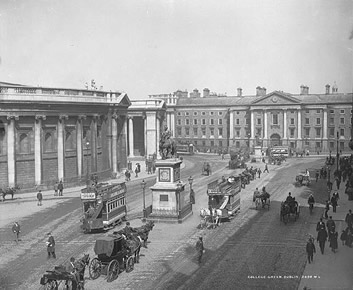

The city’s universities were also significantly divided by religion. Trinity College was founded in 1592 and was, by the mid-nineteenth century, one of the largest and most important universities in the United Kingdom, even if some Irish students did continue to study in England (see return for Read of Kerrymount, Ballybrack). In 1911 it was the most important university in Ireland and amongst its renowned fellows and scholars were Alexander O’Sullivan who lived on Ailesbury Rd., Ballsbridge, the classicist Robert Tyrell and the historians J.P. Mahaffy and J.B. Bury. In 1904 it had begun to admit women students, like Mary McKenna of Anglesea Rd., and it also continued to draw students from all across Ireland, like Hawthorne of Eccles St. and from England, like Tomlinson of Beresford Place.

The front entrance of Trinity College as viewed from Dame Street in the late 19th century. Trinity College was still the most significant university in Ireland in 1911.

(NLI, LIMP 3498)

Trinity was stagnating in terms of numbers attending, however, principally because of religious prohibitions which dissuaded the Catholic middle classes from studying there. The Irish Universities Act of 1908, which created the National University of Ireland, did much to improve the position of one of its constituent colleges, University College Dublin (see return for Colclough of Clonliffe Rd., Assistant Professor of Classics at NUI ), and gave a massive impetus to Catholic third-level education (see return for medical student at NUI, O’Meara of Lower Drumcondra Rd.). Its medical and engineering courses were particularly well thought of.

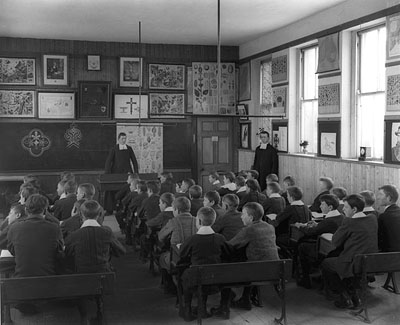

Boys from De La Salle School in Waterford listen attentively in class, 10 October 1902

(NLI, PI 903)

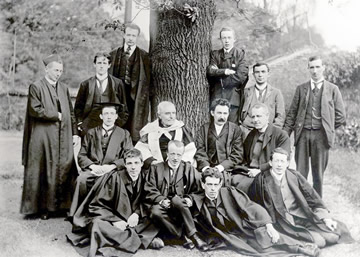

The college, on St. Stephen’s Green, was staffed by a range of excellent teachers (see return for residence on Lower Leeson St.) including Eoin MacNeill, Thomas MacDonagh, George Sigerson of Clare St. and Thomas Kettle of Northumberland Rd., who were all prominent in Irish political life. There was also a number of women staff members, including Agnes O’Farrelly (Úna Ní Fhaircheallaigh), a lecturer in modern Irish.

A UCD graduate class from 1902. Pictured among the group is James Joyce, second from left.

(Original photographs from the C. P. Curran Collection, UCD Library Special Collections. Digital images courtesy of the IVRLA, UCD)

In 1911 the Royal College of Science for Ireland moved into its new premises on Upper Merrion Street, which was designed by Aston Webb and Thomas Manly Deane. It offered courses across the range of sciences, in engineering and in agriculture, with practical laboratory work at the heart of its endeavour. Its buildings were later incorporated into UCD. Other educational institutions across the city included the Royal Hibernian Military School in Chapelizod, the Drummond Institute in Chapelizod, the Richmond National Institution for the Industrious Blind at Upper Sackville St., and a horticultural school in Clonturk.

Learning in the city was not, of course, confined to the universities. There was a growing network of libraries in the city with the National Library on Kildare Street at its core. The Public Libraries Act of 1902 facilitated the development of smaller libraries across the city. The National Museum’s collection had been expanded following amalgamation with the Natural History Museum by the addition of collections from the Royal Dublin Society (see return for Assistant Registrar, RDS, Moran of Park Avenue) and the Royal Irish Academy. The Royal Irish Academy was a significant place of learning in the capital, promoting research and publications in science, the arts, antiquities and history.

The Royal Hibernian Academy of Arts was in the process of dramatic expansion under its president, Dermod O’Brien, who had assumed office in 1910. The Royal Irish Academy of Music in Westland Row (see return for Professor Wilhelmj of Ailesbury Park)was vital in the provision of music lessons and in holding examinations. In 1911 its director was the influential Michele Esposito who lived at Sandford Rd., Ranelagh.