Government and politics

View the photo galleryIn a city so divided by wealth, class and religion, it was inevitable that politics in Dublin in 1911 were intense, bitter and utterly absorbing. From the debates conducted at public meetings and in council chambers, to the real and raw conflict of street politics, there was a vibrancy and urgency to political life. The major cataclysms of the 1913 Lockout, World War I and the 1916 Rising were all in the future, and the city was to be deeply affected by all those events. In 1911 nobody would have predicted the events of the following decade, but many of the principal players were already in place.

In 1911 primary political power in the country was rooted in the administration in Dublin Castle. Overall, government was centralised and interventionist. Formal responsibility for the administration of Ireland fell to the Lord Lieutenant, the Earl of Aberdeen, with many servants, retainers, and aides-de-camp., who lived in the Vice-Regal lodge in the Phoenix Park. He was supported by the Chief Secretary’s Office, which was charged with the business of actually running the country, with a growing body of officials (see returns for Chief Valuer Burke Gaffney, Eccles St., and for Office of Arms clerk, Bernard Tinckler of Goldsmith St.). The Chief Secretary in 1911 was Augustine Birrell.

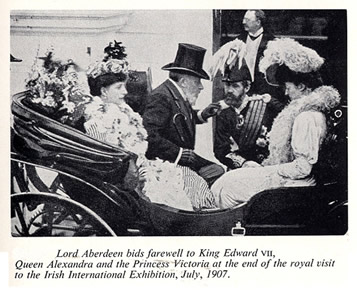

King Edward VII and Lord Aberdeen, 1907.

(taken from Vicious Circle by Francis Bamford and Viola Banks, London 1965)

By 1911 3,526 people were employed in central and local government, a ten-fold increase from 1841, with the majority based in Dublin (see return for Upper Merrion St.). From 1871 recruitment to the civil service was by open competition through exams and, by 1911, an increasing number of civil servants were Catholics (see return for Henry Charles Lynch of Simmonscourt.

Following the Act of Union in 1800, Dublin was a city without a parliament, its elected members travelling to the House of Commons in London for debates. High politics invariably focussed on the national question. In 1911 Dublin was represented by unionists and nationalists alike. The city’s best-known representative was John Dillon, living at Albert Terrace, a key member of the Nationalist Party, whose immediate objective was to win Home Rule for Ireland. Dillon was a brilliant orator who lived in Dublin as a widower, raising six children.

Also based in the city was another nationalist, a former MP, Thomas Kettle, who lived with his wife, Mary Sheehy, at Northumberland Rd. Kettle was Professor of National Economics at University College Dublin. He had been in Belgium buying guns for the Irish volunteers when the Germans invaded, and was so appalled by the invasion that he subsequently joined the British army, and was later killed in action in France.

The majority of the Dublin electorate was nationalist, but the city still returned unionist MPs, principally through Trinity College, where Sir Edward Carson, the leader of the unionists, was one of two serving MPs. Indeed, the last unionist to be elected as an MP in Dublin, outside of Trinity College, was Sir Maurice Dockrell, who lived at Belgrave Rd., Blackrock, and was elected for Dublin County in 1918.

In 1911 primary political power in the country was rooted in Dublin Castle. This photograph shows the Dublin Castle Guard

(NLI, LROY 6809)

A series of reform acts through the nineteenth century reshaped constituencies and broadened the franchise for general elections to the point where 700,000 Irishmen had the right to vote. By the end of the 1890s women had successfully campaigned for the right to participate in local elections in Ireland, and a vanguard of Irishwomen continued to fight for the right to vote in parliamentary elections. Working class women were involved, but the majority of the activists were either white-collar workers, professionals, or married to professionals.

Edith Colwill, who lived on Ailesbury Road, gave her profession in the census as ‘suffragette’. The Dublin Women’s Suffrage Association had been established in 1876 by a Quaker feminist, Anna Haslam, and later evolved into the Irish Women’s Suffrage and Local Government Association, driven by both nationalists and unionists. In 1908, the nationalist Irish Women’s Franchise League was co-founded by Hanna Sheehy Skeffington. In 1911 Louie Bennett of founded the Irish Women’s Suffrage Federation, as a co-ordinating body for the dozen or more societies active across the country. Many Irish feminists refused to co-operate with the 1911 census, as a protest against their lack of the vote.

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington with Mrs Pearse c.1921. Skeffington was a co-founder of the Irish Women's Franchise League in 1908.

(NLI, INDH 100)

Throughout the nineteenth century local elections provided the platform for a range of gains made by nationalists. In 1841 Daniel O’Connell was elected the city’s first Catholic Lord Mayor since the time of the reformation. The 1880s had brought nationalists victories in local elections as part of a revolution in municipal government. The greatest proportion of the nationalist representatives on Dublin Corporation by 1911 were minor businessmen: publicans, drapers and grocers (see return for John Farrell of Dawson St., Lord Mayor of Dublin).

A monument to Dublin's nationalist past: the statue of Daniel O'Connell on Sackville Street c. 1900.

(NLI, LROY 714)

The Corporation was not successful in addressing the great social problems which lay at the heart of city life. Some progress was made, not least in drainage, sewerage systems, water supply and the provision of electricity and street lighting, but the Corporation was badly hampered by a lack of funds (see return for Alderman Patrick Corrigan of Lower Camden St.). More critically there was no sense that the Corporation was capable of devising a policy to improve the lives of its most underprivileged inhabitants, not least because 14 of its members actually owned tenements.

It was against this backdrop that socialist politicians were attempting to organize trade unions and political parties. At their head were James Connolly, who lived at South Lotts Road and James Larkin, who lived at Auburn St. In 1910 Connolly published his seminal Labour in Irish History and also became the chief organiser of the Socialist Party of Ireland. In 1912, with persuasion from Larkin, the Irish Trade Union Congress voted to estalish the Irish Labour Party.

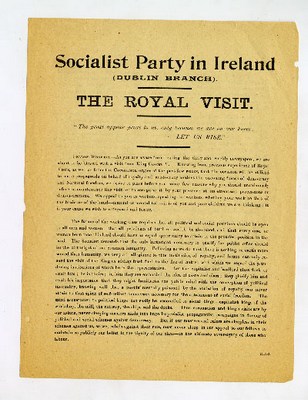

The Dublin Branch of the Socialist Party in Ireland enjoins workers to boycott ceremonies planned for the Royal visit in 1911.

(Dublin City Library & Archive, BOR F 09/05)

Within five years Connolly and his Irish Citizen Army, of which playwright Sean O’Casey, a working class Protestant who lived at Abercorn Rd., was a member, had joined with radical nationalists in the city to mount an armed insurrection. In 1911 these nationalists were very much in the shadow of their more moderate contemporaries. Though limited in numbers, their presence in the city was still considerable. Arthur Griffith, living at St. Joseph’s Crescent in Glasnevin, had founded Sinn Féin in 1905 and attracted a range of radical nationalists then operating on the fringes of Dublin life.

Thomas Clarke (see household return for St. Patrick’s Rd., Drumcondra) had been back in Ireland since 1907, following fifteen years in English prisons, and was determined to re-establish the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood as a potent force in the politics of the city. William Cosgrave, future President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State, lived at James’s St. in 1911. Eamonn De Valera, future Taoiseach and President, lived at Morehampton Terrace.

Also living in the city were prominent educationalists who were at the fore of the separatist movement. Eoin McNeill and Thomas MacDonagh were working in University College Dublin and Patrick Pearse (see household return for Haroldsgrange) had established St. Enda’s, a bilingual secondary school dedicated to the promotion of Irish culture. Their progress could be seen through the number of people who filled out the census form through Irish. Generally, this was done by members of the Gaelic League, especially teachers, like Proinsias Ua Toirnighe of Upper Drumcondra Rd.