Law and Order

View the photo galleryCrime in Dublin tended to be more associated with petty theft than with violence. The city was notable for its high level of public drunkenness and its attendant disorder. In 1910 there were 2,462 charges of drunkenness in the Dublin Metropolitan police district, while a total of 3,758 people were drunk when they were taken into custody. The nature of crime in the city was naturally reflected in the make-up of the prison population.

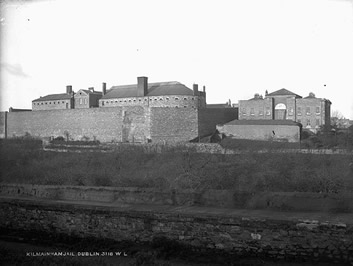

The prisons of Dublin, including Mountjoy and Gloucester St., were home to hundreds of petty criminals, invariably from the poorer areas of the city, but Dublin was not regarded as particularly crime-ridden. And it was certainly not regarded as dangerous. There was some serious crime, however, and the prison records reveal men in custody for indecent assault, conspiracy to extort money, shop-breaking, manslaughter and infanticide. As well as the prisons there was a series of reformatories across the city, including one for young girls in Drumcondra at Grace Park Road.

Dublin was the headquarters for the Royal Irish Constabulary (see return for RIC Staff Officer Moore of Hollybrook Park). The RIC was armed, wore army-style uniforms, its constables lived in barracks across the country and were subject to military drill. Its central office was in Dublin Castle, from where it was run by its Inspector-General, and its principal depot was in the Phoenix Park (see return for Sergeant Joseph Kelly of Fortview Avenue).

Dublin was also the site of the Supreme Court and High Court, which were based in the Four Courts (see return for tipstaff, 92 year-old Michael Fitzpatrick of Leo St.), a magnificent building on the River Liffey which had been designed in the 1780s by James Gandon. The lawyers who worked in the courts were increasingly moving to live in the suburbs, but a significant number still lived in the Georgian streets and squares of the city centre. Many of the lawyers who had attended the King’s Inns (see return for Cooper, wine butler at King’s Inns) to study law had done extremely well, while others were struggling (see barrister John Martin living in a boarding house in Eccles St.).

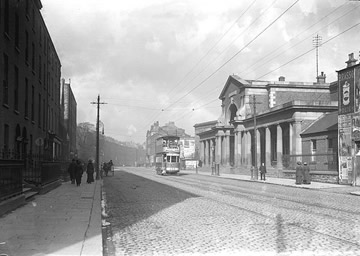

The primary law enforcement agency in the city was the Dublin Metropolitan Police (see return for barracks at Strandville Avenue, Clontarf.) which was created in 1836 and operated under the control of central government. Unlike the Royal Irish Constabulary, its members were not armed and officers were generally recruited from the ranks.

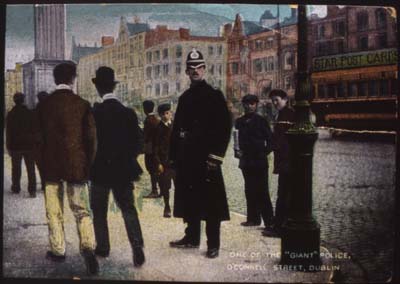

A humorous look at the police presence in Dublin, 1908.

(Dublin City Library & Archive, Dixon Slide 40.25)

'One of the "Giant" police', 1908 - Colour cartoon showing tall policeman standing on street as pedestrians pass by.

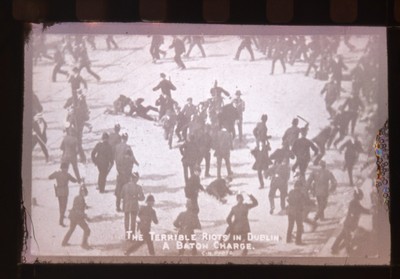

In 1911 the majority of policemen were farmers’ sons (see return for Capel St. Barracks) and they had an uneasy relationship with certain sections of the city’s inhabitants. This unease darkened into large-scale hostility after perceptions of police brutality during the 1913 Lockout. Amongst other incidents, the police baton-charged strikers along Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) and killed two men in the process.

The uneasy relationship between the police and the city's inhabitants deteriorated in 1913 when the former baton-charged strikers during the 1913 Lock-out.

(DCLA, Dixon Slides, 9.14)

As well as its regular officers, the Metropolitan Police also had an intelligence-gathering unit of detectives, G Division (see Detective Revell, who lived at Killarney Parade). This division had been centrally involved in undermining the Fenians in 1867, and in 1911, continued to play a major role in investigating political and subversive activity in the city. Among the places in which G Division took a considerable interest was the newsagent owned by IRB man, Tom Clarke (see return for the Clarke home in Drumcondra), at the corner of Great Britain Street and Sackville Street (now Parnell and O’Connell Streets, respectively).

The activities of political subversives were not nearly as central to city life as was the presence of prostitutes. Typical of any city where large numbers of men lived away from home and where female poverty was rampant, prostitution was a thriving business in Dublin. Protestant and Catholic organisations frequently attempted to close down brothels in the city and ran a number of Magdalen asylums intended to ‘save’ or ‘reform’ women who worked the streets. They had only limited success.

Brothels or ‘kip-houses’ as they were known locally were an established feature of life in tenement areas. The Monto district around Gloucester Street (see return for house in Purdon St., which may have been a brothel) was the best known home to prostitutes in the city, but there were also well-known brothels around the docks and in the south inner-city. Prostitutes also had regular standings in areas such as Grafton Street, Stephen’s Green, Sackville Street and Harcourt Street.

The women who worked in the brothels and on the streets were believed to be country girls fallen on hard times in the city, while the madams were local women. For all the condemnation of their occupation, the women were generally considered to be decent, unfortunate and kind, forced into a life on the streets through circumstance; quite a number ended up in penitentiaries like this one in High Park, Drumcondra.

The presence of so many prostitutes was determined, at least in part, by the significant military presence in the city. And the military do not seem to have disappointed prostitutes seeking business, judging by the inmates of the isolation ward at the Royal Military Infirmary. In 1911 there were thousands of troops living in Dublin in at least eight barracks across the city. At Richmond Barracks in Inchicore there was room for 1600 soldiers, a hospital for 100 patients, officer accommodation and stabling for 25 horses.

Barracks life: Troops with rifles slung over backs are put through their paces in Richmond Barracks

(NLI, LROY 11576)

At Portobello Barracks in Rathmines, there was extensive room for cavalry units, a garrison church and a canteen. Wellington Barracks on the South Circular Road had been built as a prison in 1813 but, by 1911, was operating as a barracks. The largest of all the barracks was the Royal Barracks (now the National Museum of Ireland) at Benburb Street. The Barracks had had its central portion, Royal Square, laid out in 1701 and by 1735 it could house five battalions, comprising around 5,000 men. Further squares were added over time and the Barracks was at the heart of the British military operation in Ireland.

The Royal Barracks, as viewed from the southside of the River Liffey c.1900. It is now home to the National Museum of Ireland.

(NLI, LROY 754)

Many of the soldiers stationed in these barracks were English, Scottish and Welsh, but others were locals. Irish soldiers made up a considerable section of the British Army. Recruiting sergeants, like Dower of Manor Place, and reservists, like McLoughlin of Church Lane lived in ordinary houses across the city.

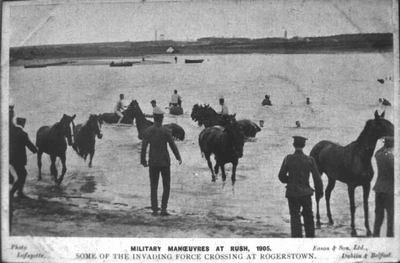

Military manoeuvres at Rush, 1905.

(Dublin City Library & Archive, Dixon Slide 39.14)

Photograph shows some soldiers on shore with others in the sea. Caption reads: 'Some of the invading force crossing at Rogerstown'

Around 130,000 Irishmen had fought in the Napoleonic wars and in the 1830s more than 40% of the British Army was Irish. By 1899 this percentage had fallen to 13% (higher than the 9% Irish share of the overall population of the United Kingdom) and it would appear that rising nationalist sentiment undermined army recruitment in the first decade of the twentieth century. The reality of poverty in Dublin and across Ireland meant that serving in the British Army was one of the few options open to Irishmen trying to earn a living, and in the course of the Great War 200,000 Irishmen served in the British Army.