Literary Life

View the photo galleryDublin produced many brilliant writers in the first decades of the twentieth century. Some, including Sean O’Casey, published masterpieces as the century progressed. Above them all towers James Joyce. By 1911 Joyce was living in exile in Trieste, but no writer has written as brilliantly about a city as Joyce did about the Dublin of that era (see return for Joyce’s father, John Stanislaus and his two sisters, living in lodgings in Gardiner Place).

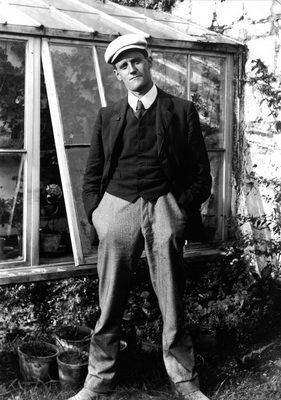

James Joyce, pictured in 1904

(Original photographs from the C. P. Curran Collection, UCD Library Special Collections. Digital images courtesy of the IVRLA, UCD)

His collection of short stories, Dubliners, published in 1914 but finished almost a decade previously, gives an expert, realistic insight into life in the city. His most famous book, Ulysses, is acknowledged by many as the finest novel of the twentieth century. Using the structure of the Homeric Odyssey, Ulysses is a remarkable journey across a city on an ordinary weekday: Thursday, 16 June 1904. Joyce’s model for “stately, plump Buck Mulligan”, Oliver St. John Gogarty, lived in Ely Place in 1911 (note his confusion about his marital status).

If Joyce was the brilliant exile who wrote beautifully of his native city, William Butler Yeats (listed as staying in Nolan’s Hotel with Lady Augusta Gregory on South Frederick St.) was the poetic genius whose overarching presence was an essential part of Dublin life as it unfolded. Joyce had exiled himself partly in reaction to the nature of literary life in the city, which he perceived to be rooted more in political oppositions than in the pursuit of artistic excellence.

William Butler Yeats, after receiving the Nobel Prize in 1923. From RF Foster, W.B. Yeats, A Life; Volume II; The Arch-Poet (2003)

Politics and theatre were entwined in Dublin. With Yeats at its heart, a national theatre movement, which saw vulgarity as an English import and attempted to promote Irish culture and traditions, was based in Dublin. Collaboration with the Fay brothers, Frank and William, led to the establishment of the Abbey Theatre, funded by patrons Edward Martyn and Annie Horniman.

Lady Augusta Gregory as pictured in Our Irish Theatre, published by G.B. Putnam's Sons, New York and London, 1914.

Lady Gregory was a co-founder of the Abbey Theatre and a driving force in the Irish literary movement

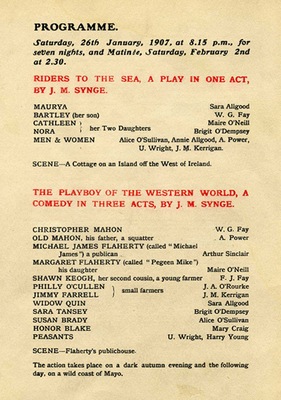

The Abbey opened in December 1904 with plays by Yeats and Lady Gregory, and thereafter theatre in Dublin remained contentious. In 1907, for example, there was organised nationalist disruption of J. M. Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World. The theatre was hugely important to the city and to the great array of actresses (Damford of Lower Abbey St.), stage assistants (Coote of Love Lane, Mountjoy), dressers (Woods of Upper Grangegorman) and attendants (Macdona of Clonliffe Rd. ) who put on plays (Downey of Corporation Buildings) .

Abbey Theatre programme for the original production of The Playboy of the Western World by J. M. Synge

(Courtesy of the Abbey Theatre)

The founding of the national theatre was part of a broader Gaelic Revival, a remarkable resurgence of interest in the Irish language and in ancient Irish folklore, songs and art, in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Although the literary life of Dublin was not dominated by the Gaelic Revival, it was redefined by it. Irish language revival societies, notably Conradh na Gaeilge (the Gaelic League), founded by Douglas Hyde (Dubhglas de hÍde) brought a resurgence in the teaching and use of Irish, and ultimately fostered a new generation of Irish writers. One of these was Patrick Pearse (Padraic Mac Piarais), who wrote poetry and prose in Irish. The extent to which poetry and politics fused in Dublin became obvious in the years immediately after 1911, with Pearse leading other prominent figures of the Gaelic Revival in political rebellion at Easter 1916.

Patrick Pearse, pictured here c. 1910, wrote and published in the Irish language and was a key figure in the Gaelic revival

(NLI, Political and Famous Figures,’ Box VI)

Throughout these years, there were many writers living in the city. They wrote in many genres, including historical novels (Hartnell of Belgrave Square W., Blackrock) and biographies (Trench of Rock Rd., Blackrock). Their works were sold by Eason's (see return for Charles Eason of Cunningham Rd., Dalkey) and other booksellers, and the making of these books gave employment to a range of people, from printers (Caprani of Merville Tce., Clontarf) to compositors (Lewis of Millbourne Ave., Drumcondra), bookbinders (Harte of Love Lane, Mountjoy), and book folders (Jevens of Lower Abbey St.)

Nationalist literary societies were prominent in the city, though many were more concerned with social gathering than intellectual discourse. In the vanguard of the cultural nationalist movement was D. P. Moran of Anglesea Rd. in Ballsbridge, who coined the phrase ‘Irish Ireland’. Moran wrote clever, scurrilous, destructive articles attacking people of all persuasions in his newspaper, The Leader. The Leader was one of a range of papers in the city, including The Irish Times, The Irish Independent and the Freeman’s Journal, all of which were aligned with one or other brand of politics.

Writing for newspapers gave employment to a large number of creative people who found work as journalists (Murray of Lomond Ave., Clontarf), sub-editors (Bunyan of Drumcondra Rd.) and story writers. And then there was the onerous responsibility of being Corrector of the Press (Collins of Lower Drumcondra Rd.). But perhaps the single most important event in 1911 for both literature and newspapers in the city was the birth, in Tyrone, of the brilliant novelist, journalist and satirist, Brian O’Nolan, later Flann O’Brien and Myles na Gopaleen.