What was Dublin like in the early 20th century?

View the photo galleryDublin, in 1911, was a mass of contradictions. A second city of the British Empire, Dublin was also the first city of nationalist Ireland and, within its boundaries, the divisions of class and culture were extraordinary. This was a city of genuine diversity, its many complexities defying easy explanations. Rich and poor, immigrant and native, nationalist and unionist, Catholic, Protestant, Jew and Quaker, and so many more, were all bound together in the life of the city.

In 1911 Dublin was moving into a decade of remarkable change; little would remain untouched. First, the 1913 Lockout redefined the nature of commerce and class relations in the city. The 1916 Rising, followed by the 1919-21 War of Independence and the ensuing civil war, turned politics and government on its head. Not all change was driven by local events. World War One saw many thousands of Dubliners fight in the trenches of Gallipoli, Flanders and the Somme. Many never came home. Those who did were often radically transformed, partly by the war and partly by what had happened at home while they were away.

Dublin Castle was the focal point of British rule in Ireland. Here is the Castle Yard as it was in the early 20th century.

(NLI: EAS 1703 )

And yet, in 1911, the notion of national independence seemed a distant illusion beside the reality of British rule. At the heart of the city stood the huge stone fort of Dublin Castle, constructed following a 1204 decision of King John, and the focal point of British rule in Ireland. Ireland had lost its parliament through the Act of Union in 1800 and all political power in Ireland flowed through the gates of the castle. In 1911 the Castle was presided over by the Lord Lieutenant, the Earl of Aberdeen, and run by the Chief Secretary, Augustine Birrell. The great administrative importance of the Castle and the government offices which stood in the most prestigious streets of the city defined the colonial nature of Dublin’s existence.

The iconic streets of Bloomsday (16 June 1904, the date on which James Joyce set Ulysses and Leopold Bloom’s epic tour of Dublin) were already being lost. The city was changing as the suburbs grew in scale and importance. Nothing transformed the physical appearance of Dublin as profoundly as the evolution in transport. Trams, horses and bicycles still dominated transport in Dublin but the private motor car was growing in importance.

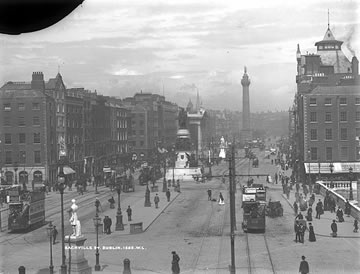

Sackville Street c.1890-1910. It was here that John Redmond unveiled a monument to Charles Stewart Parnell in October 1911.

(NLI: LROY 1662 )

Dublin was also a port city, though not in the manner of Belfast, Liverpool or Glasgow. On 1 April 1911 the Titanic was launched from the Harland and Wolff Shipyards in Belfast; no project of this scale could be undertaken in Dublin. There was no major ship-building industry, no vast industrial sector, no sense of a place driven by the impulses of manufacturing entrepreneurs and their workforce.

There was, of course, industry and innovation,, like Sir Howard Grubb’s telescope-making factory at Observatory Lane in Rathmines, but never on the scale of comparable cities in other parts of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Administration and commerce, rather than industry, were what drove the city’s economy. Dublin port was more a transit point for British goods imported to Ireland and for the agricultural export trade of the city’s rural hinterland, not least the cattle boats that left at least seven times a day, as part of the eighty weekly sailings to England.

Alongside the cattle on many of those boats were emigrants leaving a country unable to offer even the possibilities of a basic existence. Some were Dubliners, many were from the Irish countryside and were merely passing through the city, certain in the knowledge that there was simply no work available to them. Behind them they left the brutal reality of daily life for tens of thousands who lived in tenement slums, starved into ill-health, begging on the fringes of society. In parts, Dublin was incredibly poor. A notoriously high death-rate was attributable, at least in part, to the fact that 33% of all families lived in one-roomed accommodation. The slums of Dublin were the worst in the United Kingdom, dark, disease-ridden and largely ignored by those who prospered in other parts of the city.

Even for those with work, life was precarious. Trade unions attempted to organise against the backdrop of low wages and chronic over-supply of labour. On 27 May 1911 James Larkin first published The Irish Worker, the paper of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, which had enlisted 18,000 men into its ranks in just two years.

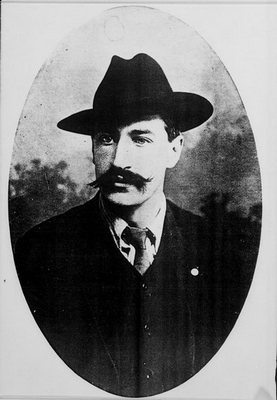

On 27 May 1911 Jim Larkin, pictured here, first published The Irish Worker, the paper of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (NLI)

Labour was growing increasingly militant, but its opponents were powerful and equally determined to resist change. William Martin Murphy founded the Dublin Employers’ Federation on 30 June. Murphy owned railways, tramways, Clery’s Department Store and, critically, the Irish Independent. The power of the employers was obvious as two major strikes during 1911, one by bakers, the other by railway workers, ended in abject defeat. As the Dublin economy continued to stagnate, strikes followed one after the next, and the greatest labour dispute in Irish history, the 1913 Lockout, was just around the corner.

Dublin politics were not often about poverty, however. Of increasing political importance were the expanding Catholic middle classes, gaining steady prominence in the city’s professional and administrative ranks. Throughout the nineteenth century, power in Dublin slowly shifted from the Protestant ascendancy to an emerging Catholic elite, who were apparently nationalist in aspect. This nationalism, however, was ambiguous in its politics and in its culture.

As the centre for British rule in Ireland for eight centuries, Dublin was the focal point of the substance and symbols of British culture. This culture – its literature, its newspapers, its sports, its music, its entertainment – was adopted with little modification by many amongst the middle classes, eager for advancement, unashamed by pursuit of prosperity.

Dublin was home to Patrick Pearse, whose work as a writer and educationalist was central to the Gaelic revival of the early 20th century.

(NLI, 'Political and Famous Figures,' Box VI)

In opposition to this, a resurgent nationalist culture was asserting itself uncertainly. Based on the premises (or perceived premises) of peasant life and traditions, revival of the Irish language, Irish dress, Irish music and Irish games, this was a resurgence which did not play easily with urban life. Dublin could not be easily accommodated in any vision which idealised rural life. And yet, Dublin lay at the heart of this Gaelic revival, home to Patrick Pearse and many of the writers, educationalists and intellectuals who recast the idea of Ireland as a sovereign Gaelic nation, free from the control of its imperial master.

Their vision was often rural, but it was not provincial. The revivalists were acutely aware of what was happening beyond Irish shores, in Europe and in North America. All told, culture in the city was profoundly modern, even an inspiration for modernism. This was the city where James Joyce and William Butler Yeats had lived and worked, and where Samuel Beckett, 5 years old in 1911, would later study. Yeats, indeed, would continue to spend a great deal of time in Dublin in the following decades. And it was also the city of Sean O’Casey and the site for the endeavours of Lady Gregory. The Abbey Theatre had been established by Gregory and Yeats in 1904. The culture of Dublin was diverse, not narrow.

The contested nature of culture in the capital was replicated in its politics. 1911 brought events which illustrated the breadth of its divisions. In July King George V spent six days in Dublin on a royal visit to the city. The King and the royal party, led by the 8th Royal Hussars on horseback, travelled from the harbour in Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire) to Dublin Castle, as thousands lined the streets to view his procession.

But, also in 1911, a Wicklow-born Protestant who was originally a strong supporter of the British Empire, Robert Erskine Childers, published his treatise, The Framework of Home Rule, which advocated the restoration of a parliament to Dublin. Childers would later be shot by firing squad by Government forces during the civil war, fought over a treaty which he was unwilling to support.

By contrast, in September 1911, the unionist leader, Sir Edward Carson, born in Dublin and still an MP elected to the House of Commons by Trinity College, told an Orange Order meeting at Craigavon House: “We must be prepared … the morning Home Rule passes, ourselves to become responsible for the government of the Protestant province of Ulster.”

And finally, in October 1911, a large crowd turned up in Sackville Street (now O’Connell St.) to see a monument unveiled to the great nationalist politician, Charles Stewart Parnell. The monument was unveiled by John Redmond, leader of the Irish national party, and its inscription was plain in its independent intent:

“No man has a right to fix the

Boundary to the march of a nation.

No man has a right

To say to his country

Thus far shalt thou

Go and no further.”

In the ferment of its politics, the vibrancy of its culture, the vertical divide of its religions, and the extraordinary disparity in its wealth, Dublin bore all the hallmarks of a city on the edge of enormous change. And the dynamic behind that change was the 477,196 people who lived in the city of Dublin and its county hinterland.