Dublin: A short history

View the photo galleryDublin’s emergence as the most important city of modern Ireland was the result a process which played out over more than a millennium of history. In 1911 Belfast had more industry than Dublin, it even had a larger population, but Dublin was the focal point of political power, the home to an elite class which ruled the country from Dublin Castle.

The city’s exact origins remain a source of dispute, obscured behind centuries of fragmented history. It is considered plausible, however, that the first stirrings of urban life came before the ninth century in the form of two proto-towns, a secular settlement called Áth Cliath, and an enclosed ecclesiastical settlement called Dubhlinn. Both settlements were based around the area where the River Poddle joins the River Liffey, close to the modern Capel Street bridge.

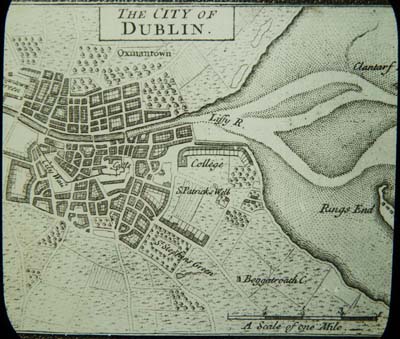

The importance of settlement at the estuary of the Liffey drew the Vikings to establish a piratical base in the ninth century and, from 917, they developed Áth Cliath as a trading centre. By the end of the eleventh century, the fore-runners of the modern network of Castle, Christ Church, Fishamble and Werburgh streets, as well as a cluster of smaller streets around High Street, were already in place.

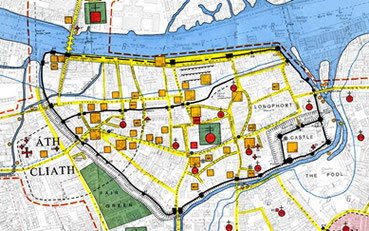

Dublin's medieval city superimposed on a modern OS map.

(From H.B. Clarke, 'Dublin c. 840 to c. 1540: the Medieval town in the Modern City' (Dublin, Ordnance Survey, 1978))

As the town grew, its importance as a trading and ecclesiastical site was confirmed. It also marked Dublin out as a prized possession. In 1170 a Norman-Irish army captured the town and, despite attempts to dislodge them, the Normans gave the town its first royal charter and it became the seat of their leader, Hugh de Lacy.

The establishment of a viable Norman lordship, with Dublin at its core, was furthered by the construction of Dublin Castle following a 1204 decision of King John. Dublin Castle, a huge stone fort, was established to administer Ireland as an entity distinct from London, with its own treasury and seat of justice.

Under the Normans, Dublin developed into a city, its importance reflected in the presence of two cathedrals and a host of large monastic settlements. The prosperity of its trading links drew up to 20,000 people to live there, before the arrival from Europe of the Black Death, the bubonic and pneumonic plague, in the summer of 1348. The population of the city was devastated and did not properly recover for several centuries, partly due to the occasional return of the plague.

Dublin was largely stagnant until the seventeenth century when profound political and religious change in Britain had enormous consequences for the city. Propelled by attempts by the state to assert its power through the courts and through parliament, as well as by a renewed prosperity in trade, the city began again to expand.

By 1700 this expansion had increased the urban population to 60,000 and this regeneration had seen the descendants of the original Norman conquerors replaced by a new Protestant elite of landed gentry, merchants, and professionals. Other Protestant migrants from England, France and Holland came to live in Dublin as a new class took control of city government.

This municipal authority, along with the increasingly powerful central government operating from Dublin Castle, oversaw a rapid expansion of the city. By the 1820s the number of people living in Dublin climbed towards 250,000. This substantial growth rested on a variety of factors – the expansion of Dublin Port as a transit point for goods, the emergence of highly-skilled trades in the city, the provision of financial services, the importance of the courts, the growth of higher education and others.

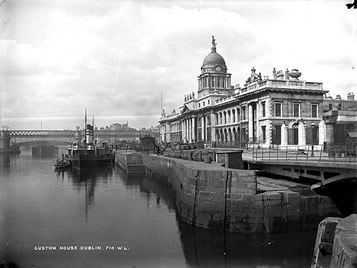

A new Dublin emerged. Two canals, the Royal and the Grand, were built and came, in time, to represent the city’s boundaries. The streets were reshaped by the Wide Street Commissioners from their appointment in 1757. Many of its landmark buildings were constructed, not least major public buildings such as the Custom House, the Four Courts, Leinster House and Parliament House, and the squares and streets of Georgian Dublin were laid out.

The James Gandon-designed Custom House, one of Dublin's landmark buildings.

(NLI, LROY 710 or LROY 711)

For all that the city expanded, essential divides remained, and even deepened. The city – just as the country – was ruled by the Protestant elite, but from the 1740s the majority of its inhabitants were Catholic. The position of Catholics in Dublin had been grossly undermined by a series of Penal Laws enacted from the 1690s onwards, which, amongst other things, prohibited Catholics from teaching and running schools, from practising law, from holding office in central and local government, from standing for Parliament and even from voting. Accordingly, the gentry, the professional elite of lawyers and doctors, and the city’s most prosperous merchants, were almost invariably Protestant.

By contrast to the lives of the Protestant elite, the great mass of the Catholic majority lived in an entirely different type of city, grossly underprivileged in income, education and political power. Not all – or even most – Protestants were wealthy, of course, and Dublin was the setting for occasional sectarian conflict, particularly between gangs of young men.

Villages like Rathmines, photographed here at the turn of the 20th century, prospered with the flight of wealth from the city to the suburbs.

(NLI, LROY 5953)

The story of the nineteenth century is one of the steady erosion of the power of the Protestant ascendancy. Catholic Relief acts in the last two decades of the eighteenth century repealed many of the Penal laws which discriminated against Catholics. In the aftermath of the Act of Union in 1800, Catholics continued to fight for the right to hold political office and having secured this ‘Catholic emancipation’ in 1829 used it to claim a measure of municipal power in Dublin city. Dublin remained a colonial capital, but as the century progressed, the Catholic professional and business classes had taken control of city government.

This control did not bring renewed prosperity. Dublin stagnated and did not industrialise in the same manner as Belfast or the northern cities of industrial England. The bulk of the city’s people lived a precarious existence in high-density, poor-quality housing, surviving on the low incomes earned from casual labour. Ill-health was endemic and mortality rates extremely high. The nationalist Dublin corporation proved singularly incapable of successfully addressing the poverty that spilled all around the city. The emergence of the trade union movement spoke eloquently of looming crisis.

By 1900 Belfast, driven by its industrial engine, had grown to be the largest city in Ireland. Despite its thriving breweries, distilleries, and sundry other smaller industries, Dublin was not flourishing. Its wealth was further dissipated through a flight of the middle classes towards the outer suburbs and outlying villages. There, the formation of ten townships, independent of the city, was facilitated by the arrival of rail and tramways to serve the first commuters.

In the early twentieth century, Dublin remained a hugely important political, commercial and cultural city. It was, nonetheless, a city notable for the underlying tension and restlessness so typical of places profoundly divided by wealth, class and religion. Its long history had left Dublin ill-prepared to deal with the demands of the twentieth century.