City Transport

View the photo galleryIn 1911 Dublin was served by an impressive public transport system and was also beginning to cater for the demands of the city’s increasing number of private motorists. As well as its internal transport network, Dublin was also the focal point of the national system, a vital hub in the commercial and social life of the country. The iconic means of public transport of the time was the Dublin tram. The electrified trams of 1911 had replaced the original horse-drawn trams, which in turn had replaced the horse-drawn omnibus.

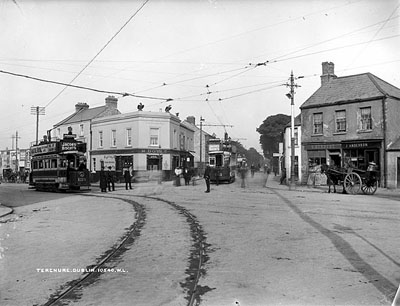

There were, by 1911, 330 trams (see return for tramway official Maher of Shelbourne Road) operating on lines which ran for 60 miles along the city’s roads, drawing the suburbs tightly to the city. It was believed by Dubliners that many of the people who came to work for the tram companies were from the country, like Duffy of Killarney Parade.

Two trams meet at a Terenure crossroads c. 1900. There were 330 trams in operation in 1911.

(NLI, LROY 10540)

C.S. Andrews claimed in his book, Dublin Made Me, that the Dublin United Tram Company had a policy of recruiting non-Dubliners. In part this was because the original trams were horse-drawn and reflected the ability of country people to work with horses. But the trend was thought to have continued, and many of the tram drivers and conductors living in the suburb of Terenure were originally from Westmeath.

People working for the rail companies also tended to cluster in certain areas (see return for Courtney of Phibsboro Road). There were numerous examples of this including the houses on Great Western Square off the North Circular Road which were occupied by employees of the Midland Great Western Railway. The numerous jobs associated with the railways ensured that people who worked for them had a presence all over the city (see return for Fagan household, Coburg Place), and there were also many people who owed their living to money made from investing in the railways (see return for Kennedy of Priesthouse, Donnybrook).

The first railway line in Ireland had opened on 17 December 1834 when the Dublin city centre station of Westland Row was linked to the coastal port of Kingstown (later renamed Dún Laoghaire). The railways were important to the development of suburban Dublin in their facilitation of commuters travelling to work in the city centre (see return for Redmond of Mellifont Avenue, Kingstown). By the end of World War I there were over 3,500 miles of railway in Ireland, with Dublin as the focal point of the network. The populariity of the links from Dublin is demonstrated by the adding of a second storey to the Kingsbridge station in 1911.

A postcard advertises the joys of rail travel for Dublin day-trippers c. 1900

(Dublin City Library & Archive, Dixon Slide, 40.34)

Postcard read: 'Kingstown: By rail from city (Westland Row) in 15 minutes. Delightful trip by electric tram, fare 4 d.' c. 1900

A mutually beneficial leisure industry developed in tandem with the railways (see return for Strand Ranger Anderson of Danespark, Clontarf). The expanding middle class adopted a culture of travel and daytripping which benefited Dublin coastal villages such as Blackrock (see return for Peoples’ Park keeper Butler of Rock Road, Blackrock) and Kingstown. Seaside resorts grew and race meetings were established, along with a host of other sporting events such as regattas and galas (see return of yachts in Kingstown Harbour).

The importance of the railways extended even to the notion of time in the city and beyond (see return for Timekeeper Ducie of Mounttown Cottages). The development of railway timetables was critical to the passing of the Time Act, 1880, establishing Dublin Mean Time across Ireland. Previously, clocks in Cork were eleven minutes behind those of Dublin, while those in Belfast were one minute and nineteen seconds ahead. In 1911 Dublin was still 25 minutes behind London, and it was only in 1916 that Greenwich Mean Time was extended to Ireland.

The motor-car age: a 20 hp Panhard with driver and four passengers turns off Stephen's Green c. 1897-1904.

(NLI, CLAR 21)

Ireland had been to the forefront of the cycling craze (see return for cycle depot manager Rollins of Haddon Road) which swept the western world in the late Victorian era. It wasn’t merely that the Irish adopted the bicycle (see return for cycle and motor mechanic John Keogh of Clarendon St.), they also contributed to its development. John Boyd Dunlop invented the pneumatic tyre in the 1880s after his son had complained of the pain caused by cycling on solid wheels over cobblestones. The tyre was an immediate success and Dunlop went into business with Harvey du Cros, a paper manufacturer of Huguenot origin, manufacturing the tyres at Stephen’s Street in Dublin. All across the capital, the tyres were fitted on the growing number of bicycles seen along the city’s streets (see return for Moore gun and cycle maker at Summerhill Place).

Like all other modes of transport, the bicycle came under pressure following the arrival of the motor car. The remorseless twentieth-century rise of the private car in Dublin had already begun in 1911 (see return for Michael O’Brien of Bath St., bread van driver). In that year there were a total of 5,058 registered cars, buses and lorries in Ireland, a large proportion based in Dublin (see return for Kearney of Prince Patrick Lane, licensed car owner). Various coachbuilders had adapted their manufacturing plants to build car bodies, including Huttons.

The first petrol car seen in Ireland was owned by a Dubliner, Dr. John Colohan, who imported a Benz Velo in 1896. He was quickly followed by other prominent Dublin citizens such as H.M. Gillie, the editor of the Freeman’s Journal, and Lord Iveagh. When the Royal Irish Automobile Club (see return for Rudden, Dawson St., caretaker of the Club) was founded in 1901, the majority of its members were titled landowners, military officers, or wealthy brewers and distillers. Another was Richard J. Mecredy, a leading cyclist and athlete, who established a newspaper called Motor News.

Kingstown was the first suburb to be linked by rail to the city centre and it became a focal point for day-trippers

(NLI, LROY 689)

In time the roads of the city facilitated the further development of the bus as a means of public transport but, in 1911, the remnants of the old tradition of jaunting cars remained prominent. Four passengers sat back-to-back, two on each side as the horse-drawn carriage moved through the streets. It was a tradition that survived well into the twentieth century. Tradition and modernity lived side-by-side, not least on Gardiner Street where a harness maker Jackson lived next door to a motor driver.