Dublin Waters: the Liffey, the canals and the port

View the photo galleryIt was the River Liffey and its estuary which drew the first settlers to build the communities which became Dublin. In 1911, more than a millenium later, the water which flowed through and around the city continued to have a huge impact on the life of its inhabitants. By 1911, all the quays of the Liffey, stretching from Kingsbridge Station (now Heuston Station) to the port had been laid out, and the older ones had been renovated in the preceding decades. The building of the quays was a formidable feat of engineering and critical to the preservation of bank-side land from the periodic flooding which had blighted its development.

Along the quays were some of the landmark buildings of Dublin, not least the Custom House (see return for caretaker, Edward Francis Baker ) designed by James Gandon. Other buildings were not as architecturally important, but were connected with sea and river life. There were dedicated home for sailors (see return for Supervisor of home at Sir John Rogerson’s Quay ) and seamans’ institutes (see return for caretaker at Eden Quay). Also on the quays was Moira House which was built in 1752 by Sir John Rawdon. In 1911 the house was being used by the Association for the Suppression of Mendicancy in Dublin as a hostel for the alleviation of street begging.

The last of the quays to be completed was Victoria Quay, which was named after Queen Victoria in 1863 when she opened the bridge which joined it and Albert Quay (now known as Wolfe Tone Quay). Every street which ran down to the Liffey was filled with men who laboured on the docks whenever work was available (see return for Kavanagh of Sandwith Lane). And, of course, there were the pubs on the quays, where working-class men sought refuge from hard work and poverty, and where dockers were traditionally paid by the stevedores who controlled their employment (see returns for McGreevy's and Moore's, both on Eden Quay ).

The Liffey and its reservoirs were a vital source of water for the city. Naturally, the Liffey, in the tradition of rivers in almost every major city, was also a much-used dumping ground for sewage and for the city drainage system. In 1906 the first major drainage system was completed and sewers which had previously discharged crude sewage into the Liffey were now intercepted and their content brought in pipes laid along the quays to a treatment works at Pigeon House (see return for Drainage Officer Costello at Ringsend) on the south bank of the port.

Crossing the Liffey was often an expensive business. Many of the bridges were tolled and even in 1911 Wellington Bridge still had turnstiles, which were not removed until 1919 when the bridge was opened free to the public. Its toll endured in the public consciousness and it has retained its popular name: the Ha’penny Bridge. Those who did not cross by bridge often used the ferries (ferry boatman Thomas Aspill) which plied their trade downstream from the main retail areas of the city. Through the late nineteenth century there were complaints that the boats, which were generally rowed across, were often overcrowded, carrying more than thirty people. By 1911, all five ferry crossings which survived were driven by motors; they were a vital link for communities and businesses at the port end of the Liffey (see return for sea lock-keeper Prendergast of Spencer Dock Cottages ).

Other rivers also held great attraction for Dubliners as places to fish, to walk alongside, or even as iconic names in song and verse. The second largest river in the city is the Tolka, which rolled through the agricultural lands to the west of the city before passing through Cabra, Glasnevin, Drumcondra and Ballybough before entering the Irish sea at the East Wall and Clontarf. The Dodder flowed from the northern slopes of Kippure in the Wicklow mountains, before winding its way through some 20 km through Tallaght, Rathfarnham, Clonskeagh, Donnybrook, and Ballsbridge. It entered the Liffey at Ringsend.

For many years, the Poddle provided drinking water for Dublin. Rising in Fettercairn, near Tallaght, it ran through the outlying village of Templeogue and then through the heart of the old city. By 1911 it crossed underground through Dublin Castle, from the Ship Street gate to the Chapel Royal, and then northwards to the Undercroft. It flowed into the Liffey at Wood Quay.

The port itself was critical to the economy of the city. It did not industrialise as intensively as the ports of Belfast and Liverpool or Glasgow and, in 1911, only had a very small-scale shipping industry run by the Dublin Dockyard Company (see return for shipbuilder Smellie of Hollybrook Park, Clontarf ). There were sailmakers (Redmond of Summerhill) marine stores on Church St. and a whole range of trades which grew around the port (see horse-dealer Nugent of Church Road).

There was also a traditional glassmaking industry in the Ringsend area, and sundry other manufacturing concerns around the port. If the port was limited in terms of manufacturing industry, it was, nonetheless, an absolutely vital trading post for the city and its hinterland (see return for steamship agent Francis Egan of Hollybrook Park).

The trade in imported and exported goods was critical in providing employment for the working-class areas of Ringsend, Irishtown and the North Wall. There were sea captains (Jevens of Lower Abbey St. and Baker of Eden Quay) carters (Malone of Eccles Place) and crane drivers (Keely of Church Place), shipwrights (Quinn of Millmount Avenue), marine engineers (Murphy, also of Millmount Avenue) and fish merchants (Watson of Eden Quay.

In every trade there were many struggling to find work (see Michael O’Brien, of Church Place,). As the nineteenth century progressed, increasing quantities of British-manufactured goods made their way through the port, as did large shipments of coal. Dublin’s position as the focal point of the rail network confirmed the importance of the port as a point of import.

However, Ireland was unable to export much by the way of manufactured produce with the notable exception of Guinness (see return for employee Byrne of Harold Road), Jacob’s biscuits (see return for Kathleen Regan of Bishop St., “factory giral”) and a small number of other sought-after items. The bulk of Irish exports were agricultural, and every day shipments of cattle left Dublin port for English farms and slaughterhouses. From the 1870s on seven shipments a day left for British ports, with even more sailing between September and March(see return for Doyle of Church St., who was a fireman on a steamboat).

The transportation of people formed a large part of the activity of Dublin port, which was the point of departure for tens of thousands of Irish people who were emigrating (see William Birch, Master Mariner on City of Dublin Steam Co. mail service) There were also migrants arriving and emigrants returning, but the numbers leaving were far higher.

Similar scenes were witnessed south of the city, where the Dublin Steam Packet Company operated the Kingstown to Holyhead mail and passenger route (see return for porter Carroll of Coady's Cottages). Overall, by 1911, there were more than 80 cross-channel sailings per week to Britain (see return for sailor Penston of Mounttown Cottages).

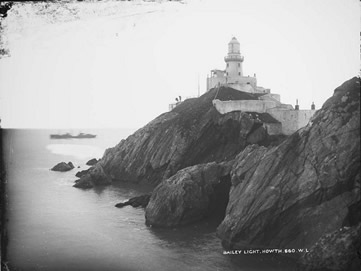

For many leaving Ireland, the last sight of land came from the lighthouses along the coast. These were the responsibility of the Commissioners of Irish Lights from 1867, and among the permanently manned lighthouses around the Dublin coastline were the Poolbeg Lighthouse (Byrne) and the Baily Lighthouse at Howth (McCann of Howth Hill). Lighthouses were critical to those who made their living from the sea, not least the many fishermen who fished the waters of Dublin bay.

There were fishing communities all along the coast of north county Dublin. Communities such as Loughshinny depended on the earnings of such fishermen (Attley), as well as being home to the coastguards who patrolled the waters (McDonnell). The Royal Navy, too, had a significant presence in Dublin bay (see return for George Ward Earle of Atmospheric Road, Dalkey, Chief Waiter, Royal Navy).

Howth and other Dublin coastal villages such as Clontarf, Blackrock and Kingstown were also renowned as seaside resorts (see return for Strand Ranger Anderson of Dane's Park, Clontarf), for those with money to spend on leisure. Kingstown, for example, was fashionable for its yachting (see return for yachtsman Davy of Pembroke Cottages) and other maritime activities, including swimming at the ‘forty foot’, a small natural harbour at Sandycove, popular with generations of Dubliners.

The beaches along the Dublin coastline provided leisure opportunities for Dublin families. This photograph shows children paddling in shallow water c. 1890-1910.

(NLI, CLAR 29)

As well as yachts and other pleasure boats, there were many row-boats listed as pleasure crafts moored in the harbour. All along the coast, north and south of the city, small villages prospered from the growth in local tourism and leisure outings. The River Liffey was also a focal point for fishing, rowing clubs (see Dolphin Rowing Club) and swimming. It, too, developed its own recreational importance, and in 1910 a new hotel and sanatorium were opened on its banks by the Lucan Hydrophatic Spa company.

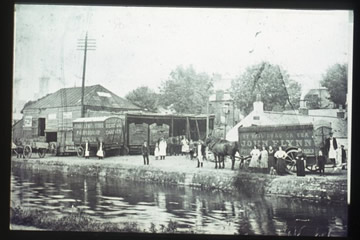

Hotels had been a significant feature of the development of the canals which left Dublin. The Royal Canal (see return for four canal boatmen at Rinsend Basin) ran from Dublin to Mullingar, with offshoots running to the Shannon at Cloondara and to Longford. It was bankrupted before its completion around 1817 and never proved as profitable as the Grand Canal, which linked Dublin to Shannon Harbour in 1805.

The Royal Canal, pictured here c. 1902, marked one boundary of inner-city Dublin. The Grand Canal marked the other.

(DCLA, Dixon Slide 29.11)

As well as a string of hotels, the canals facilitated the development of breweries, distilleries and other industries. Initially, canals provided for more efficient transport of goods and passengers than existing modes of transport, but by 1911, they had been largely surpassed by road and rail. The canals remained a focal point of the city and were seen to mark the boundaries of inner-city Dublin.