Economy and Society in Galway in the early 20th century

View the photo galleryIt is impossible to escape the reality of poverty in Galway in 1911. The workhouses were filled to overflowing (see first page of return for Galway city workhouse), the rate of emigration from the county was steep and many of those who remained were engaged in a persistent struggle to remain above water. There were many within the county who could simply find no work at all (see John Cosgrove, unemployed railway conductor of Derrybeg).

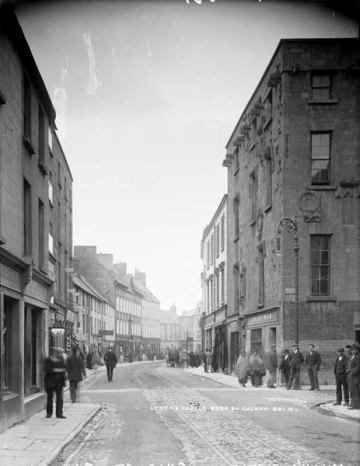

There was, of course, some measure of prosperity. In Galway city and in the towns of the county there were the usual collection of shopkeepers (see Michael Goggins in Tuam) and skilled workers such as tailors and carpenters (see return for Bartley O’Malley of Moneenpollagh). The city was primarily a mercantilist centre dominated by families like the McDonoghs. Martin McDonogh was one of Galway’s primary entrepreneurial figures, chairman of the employers’ federation, the Urban District Council and the Harbour Board.

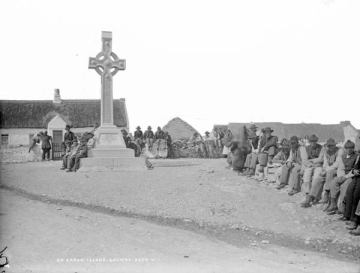

There was also a range of government employees, from local government staff to firemen (see return for John Cahill in Ardrahan and policemen (see return for Newford RIC barracks near Athenry). Important fisheries were based along the coast and many made their living from the sea (see return for Martin McDonogh at Inishmore). The beauty of the Galway coastline and the arrival of the railways in the second half of the nineteenth century helped develop the county as a tourist destination, again giving employment in the region, including this hotel in Roundstone

Amongst women who were working, the census records that 30% were working in domestic service (see return for Margaret Baker in Ballinasloe). Others worked as charwomen, dressmakers (see Kate Lydon in Tuam) and as seamstresses (see Mary O’Malley in Galway City).

For all that there was employment in fishing, in tourism and in the towns, Galway was primarily an agricultural county and the land (see Luke Duffy and his family at Eyrecourt) was the principal focus of economic life in the county.

Disputes over land in the county had been a focus of social unrest dating back to the days of the Land League and the Plan of Campaign. The county was home to the famous Clanricarde Estate (see return for Edward Shaw Tenor, living in Portumna Castle in 1911), extending over 50,000 acres in East Galway, which was a by-word for controversy. The estate was finally bought out in 1915. But there were other estates too (see return for the Honourable Robert Dillon of Clonbrock Demesne) and disputes over land were a staple of life in Galway.

Lough Cutra Castle in Gort, east Galway. This magnificent home was built during the 19th century

(NLI, LCAB 03923)

It was a Galway landlord, John Shawe Taylor, whose letter to the press provided the impetus for the great land conference which led to the Wyndham Land Act of 1903. That Act was buttressed by a further act in 1909 but cattle grazing (see two herdsmen in Beaghmore) remained a deeply controversial subject, particularly in the east of the county, even as the Land Commissioners and the Congested District Board facilitated the passage of estates to their tenantry.

By 1911 over 3500 holdings, comprising of 75,000 acres, in the county had been vested in their tenantry at an average price of £333, though many large estates remained (see Algernon Persse of Cregalclare Demesne). Nonetheless, parliamentary figures for 1911 indicated that almost 30% of national instances of ‘boycotting’ took place in the county. In 1911 Galway was one of the few counties still proscribed and there were approximately 1,000 police in the county (see Robert Jones, RIC pensioner and family at Ardrahan).

The lust for land was rooted in an instinct for survival. Following the decimation caused by the Great Famine of the mid-nineteenth century the county remained susceptible to periodic famine. Regional food shortages recurred between 1858 and 1862 and again between 1879 and 1882. Prior to 1911, the last such outbreak was in 1904, and there were problems again in 1912.

In 1911 the number of people in the county receiving relief under the poor law system was 2,614, of whom 1,301 were in workhouses (see return for Tuam Workhouse) and 1,313 received outdoor relief.

The census reports also recorded the number of emigrants from the county in the ten years between 1901 and 1911. A total of 24,464 people (11,676 males and 14,788 females) left Galway during this time.This represents a considerable decrease over previous decades; the comparable figure for the decade ending in 1891 for example was over 50,000.

The prospects of those leaving the county were improved by the education they had received. Free primary education after 1831 and the enforcement of compulsory education for children between the ages of 6 and 14 in 1892 ensured that all Irish children had access to a basic level of education, at least in theory. In Galway in 1911, 31,130 children are recorded as attending school (see return for teacher Deborah Caulfield at Ballinasloe), an increase of 1432 over the same figure in 1901.

Letterfrack Industrial School ca. 1900. Situated in Connemara, more than 80 kilometres from Galway city, the school opened in 1887 and was run by the Christian Brothers.

(NLI, LROY 05373)

Over 78% of the population are recorded as literate, 2% as being able only to read and almost 19% were illiterate (see return for James Holleran of Glenamaddy, with his mark inserted in his name at the bottom of the page). Most of those who could not read and write came from an older generation who had not enjoyed the benefits of a national school education (see Bridget Cosgrove of Killereran).

The number of Irish speakers is recorded as 98,523 of whom 7,811 spoke Irish only (see Patrick Duffy of Cong, who was also deaf) and 90,712 regarded themselves as competent in both Irish and English; 54.1% of the county population recorded competence in Irish.