What was Galway like in the early 20th century?

View the photo galleryGalway in 1911 was a county in decline. Its population had fallen to 182,224 in the ten years after 1901, a decline of just over 5%. This fall was the latest in a calamitous chain of decades which had seen the population of Galway collapse from a pre-famine peak of 422,923 to 182,244. The rate of births and marriages were considerably below the national average. As if to emphasise the social and economic malaise in the county, Ballinasloe was the only district – rural or urban – to record an increase in its population over the previous census. The town’s population increased from 4,904 to 5,165.

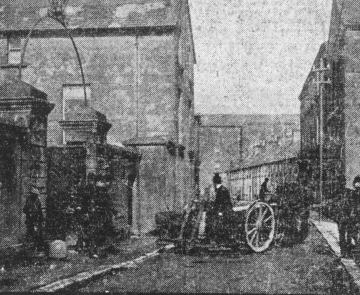

Society Street, Ballinasloe, Co. Galway ca. 1900. Ballinasloe was the only district - rural or urban - to record an increase in its population between 1901 and 1911.

(NLI, LROY 08040)

It was not just that the population of Galway was falling, the scale of urban living provided evidence of the problems facing the county. The county was predominantly rural. Indeed, while much of the rest of the western world was urbanising, the population of Galway city was actually falling – from 13,426 in 1901 to 13,255 in 1911. Outside of Galway city, there were only three towns in the county: Ballinasloe, Loughrea and Tuam.

Potato digging in Galway ca. 1900. At the time, agriculture was the mainstay of the local economy

(NLI, Clon 739)

The falling population of Galway city was rooted in a failure to develop a meaningful industrial base. Existing industries endured a somewhat precarious existence. The city’s industrial base had been undercut with the closure of Persse’s distillery in 1908. The famous Claddagh fishing industry was also in decline following the onset of modern trawlers. Ultimately, the city was primarily a mercantilist centre dominated by families like the McDonoghs (See return for McDonoghs in Flood St.)

Persse´s distillery, which closed in 1908.

(http://places.galwaylibrary.ie/history/images/large/perssesdistillerynunsisland.jpg)

That is not to say that the nineteenth century had been entirely without economic progress. The Royal Galway Institution, which became the Chamber of Commerce in 1923, had been established in 1839 to promote ‘arts, agriculture and manufactures’. The Eglinton canal which connects the River Corrib to the sea was built in the 1840s. The Dún Aengus port development was completed in 1883, capping a 50-year period of docks development. Not all of the developments around the port were positive. Questions were asked in the House of Commons in London about an outbreak of beri beri on a Norwegian ship docked in the city. More happily, in 1907 the first commercial transatlantic telegraph service connected Clifden to Glace Bay in Nova Scotia. It was initiated by Marconi’s wireless and telegraph company

The Marconi Station at Clifden, Co. Galway. The Marconi wireless and telegraph company established the first commercial transatlantic telegraph service, connecting Clifden to Glace Bay in Nova Scotia in 1907.

(NLI, LROY 05350)

Galway was home to an Irish industrial exhibition in 1908, the first such exhibition held in Connacht.. This was attended by representatives of the city’s tribes. It focussed on the display of native Galway industries and the potential for agricultural improvement based on overseas practices. King Edward had visited the town in 1903 as part of his Irish tour, reportedly the first ever trip west of the Shannon by an English King. He received a warm welcome.

Indeed, the beauty of the Galway coastline and the stunning scenery in Connemara brought a burgeoning tourism industry. Salthill, a seaside resort close to Galway city, had developed as a tourist attraction. This was certainly aided by improved infrastructure, both in and to Galway city. A horse-drawn tram had been established by the Galway Omnibus company in 1895 to run out to Salthill bringing significant numbers of people to the seaside.

The Great Western Railway company had already extended its line from Dublin to the county in 1851. This had opened up the region to tourists. The rail line was extended in 1895 further westward to serve Connemara and Clifden. On a further positive note, in 1911, the rail line was extended to facilitate mining at Shantalla. A by-product to this development, however, was the opening up of the regional market to cheaper imports which decimated local manufactures.

Ironing the land: a small railway station at Ballinahinch, Co. Galway at the turn of the 20th century

(NLI, LROY 11132)

The Galway newspapers throughout 1911 were dominated by issues such as the possible re-establishment of Galway as a transatlantic port. The city had had an on-off service over the previous fifty years. The Allan Line operated a service between 1880 and 1905 primarily facilitating the departure of emigrants and the delivery of mail. There were also calls for the extension of a telephone trunk service to the city, as the existing service in Ireland went no further west than Athlone.

A positive development in the early years of the twentieth century was the establishment of University College Galway following the implementation of the National University Act of 1908. The college had opened in the 1840s as a Queen’s College, but had been rejected by the Catholic Church to the extent that it was once described by Gladstone as ‘a derelict college in a derelict town’. The change in 1908 produced immediate signs of life following its new-found acceptance in the Catholic community.

The importance of acceptance by the Catholic community was obvious. The census shows that in 1911 97.6% of the population were Roman Catholics. The Catholic diocese of Galway had been established in 1831. The Pro-Cathedral in Middle Street was built between 1816 and 1821. The older Tuam diocese was home to some of the country’s most prominent churchmen including Archbishop McHale and Archbishop William Walsh. Its magnificent cathedral dated to 1836, while St Brendan’s Cathedral in Loughrea had been opened in 1903. The diocesan college, St Mary’s, opened a year after the 1911 census.

An exterior view of St. Jarlath´s Cathedral, Tuam. In 1911, almost 98% of the population in Galway were Roman Catholics

(NLI, LROY 06755)

The great majority of the remaining 2% who professed other religions were Church of Ireland, though there were also a small number of Methodists and Quakers. In the course of returning their census forms 23 persons declined to answer the question on religious affiliation.

Institutions run by the church gave succour to the poor of Galway but so, increasingly, did state moves to improve the lives of the people. The year 1911 saw the passing of the Labourers (Ireland) Act to assist the housing of urban labourers, and by the following year over £1300 had been allocated to Galway. Other legislation which also impacted on the county was the Old Age Pensions Act which, although official county figures were not recorded, led to 3,000 census search applications from the county in an effort to determine eligibility. The year 1911 also saw the passing of the new National Insurance Act, and the Chairman of Galway County Council, Joseph Glynn, was appointed chairman of the Irish Commissioners. Galway was one of the first counties to apply for a sanatorium under the Act.

More than anything, though, Galway remained a county dependent on agriculture. It speaks volumes for the scale and intensity of disputes over land in the county that in 1911 Galway was one of the few counties still proscribed. Indeed, parliamentary figures for 1911 indicated that almost 30% of national instances of ‘boycotting’ took place in the county. The lust for land was rooted in a basic desire for survival. The Great Famine had wrought appalling damage on the people of the county and was just a lifetime past. Its memory – and ongoing food shortages – were acute and informed the organisation of agriculture in the county.