Economy and society in Waterford in the early 20th century

View the photo galleryEmployment in Waterford was revolved around farming and on the sea (see household of Richard Bell in Passage). Agriculture was dominated by tenant farmers (see Condon family near Youghal, though there was also employment for a dwindling number of farm labourers (see Patrick Baldwin at Carricklong). Farmers lived even in the city of Waterford (see Thomas O’Meara at Grattan Quay). Inevitably, of course, the city of Waterford was home to numerous cattle dealers (see return for Hayden’s Hotel on Merchants’ Quay, full of cattle dealersand there was a huge export trade in live animals from Waterford port.

A group of officials (foreground) and members of the R.I.C. along with Mr. Mansfield (2nd left by gate) at Mansfield´s farm, Crobally, Old Parish ca. 1910. The photograph was taken during a dispute over a well.

(Waterford County Museum, EK 158)

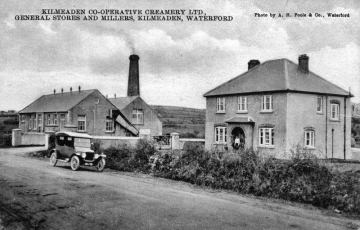

In an attempt to promote agricultural industry, small groups of dairy farmers and others employed in related work established co-operatives around Waterford. They were inspired by the advocacy of Sir Horace Plunkett (see return for his household in Stillorgan, Dublin), who called for the establishment of co-operative ventures where people would buy shares and set up their own businesses which would be run by committees elected by themselves. The first co-operative creamery owned and run by farmers was established in Limerick in 1889. The movement spread to Waterford when a creamery was established in Gaultier in 1894 and another was established in Ballinamult in 1895. Amongst the pioneers in establishing a co-operative creamery in Kilmeaden were Charles Stephenson from Fairbrook, Guss Goff from Ballyduff East, and Joseph Walters from Bawnfune. After intensive planning, the Kilmeaden Co-operative Creamery took in milk for the first time in October 1916.

Pictured on the left is the Kilmeaden Co-operative Creamery ca. 1910. The founding of co-operatives by dairy farmers and others was an attempt to promote agricultural industry.

(Waterford County Museum, UK2815)

There were other industries in the county. By the middle of the nineteenth century the village of Portlaw held more than 5,000 inhabitants. Its cotton mill employed a workforce of 1,800. As well as local people, there were migrants from Belfast and from the northern industrial towns of Lancashire and Yorkshire in England. The collapse of the cotton mill left the town bereft of significant employment and the population fell to just 2707 in 1911. Later, in the 1930s, part of the cotton mill was used to establish a tannery in the town.

Trade in Waterford was dominated by family businesses. For all that the county was predominantly Catholic, many of the leading families in business were Protestant or Quaker. Through the second half of the nineteenth century and on into the early decades of the twentieth century the Chapmans of John’s Hill ran a prospering wholesale and family grocery on O’Connell Street in Waterford city. Coad’s, the largest boot and shoe retailer in the city, was owned and run by a family of Methodists, the Coads of Ballymaclode. Merry’s wine and spirit merchants was run on the Mall by two Presbyterians, Robert and Euphemia Merry.

A group of assistants, all workers at the Home & Colonial Store on Broad Street, 10 May 1910

(NLI, P WP 2028)

Other industries included several meat companies. The firm of Henry Denny and Sons dominated the bacon and sausage markets for many decades after its establishment in 1820. Bell’s Chemists was both a retail premises on Quay Street in Waterford city and a large pharmaceutical factory (see return for employees) based in Exchange Street. There was also significant employment at the Waterford brick factory (see the very large Poole family of Barker St.).

And the iconic Waterford company – Waterford Glass – which was started by the Penrose family had prospered, then failed, only to prosper and fail again in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Waterford had a thriving retail sector. There were numerous drapers (see Thomas Murphy and his staff on Coal Quay), the most prestigious of which was probably Robertson, Ledlie, Ferguson and Co. (see Ledlie family in Tramore) which was based at 53 and 54 The Quay in Waterford city. There were also confectioners (see Mary Fahey on Parade Quay), tobacconists, grocers, butchers and publicans (see Anna Dowling, John Higgins, James Cummins, and Mary Ellen Pond all on Merchant’s Quay), plasterers (see John Bohill on Main St.), Tramore, blacksmiths (see Thomas Dunne on Henry St.), dentists (see William Meredith of Parade Quay),oil company directors (see William Poole of Newtown Rd.) and men selling everything from stocks and shares (see James Whitty of Merchant’s Quay) to soap (see Edward Downey of Priests’ Road).

Age-old skills survived in the city, including men who made boots (see Peter Bowe at Custom House Quay), harnesses (see Cornelius Halpin at Merchant’s Quay), shoes (see Patrick Busher at Custom House Quay) and watches (see Stuart Davidson at Custom House Quay) and ships’ pilots (see James Bell of Passage). There were newer industries employing telegraph clerks who worked out of the General Post Office. There were also photographers (see Henry Holborn at Mall Lane, most notably the Poole family who lived on the quay next to Reginald’s Tower. Their photographs offer a magnificent record of life in Waterford in the decades either side of 1900.

The state was also a big employer in Waterford, where there was a significant army (see return for Infantry Barracks on Barrack St.) and police (see retired RIC Head Constable, Gilbert Boardman, on Patrick St.) presence. Across the county was a necklace of police barracks (see RIC barracks on Queen St., Tramore), and this being a significant sea-going county, there was also the coast guard (see Edward Dunnett at Love Lane in Tramore). Still more were employed as clerks (see Louis Lotzrich on Parade Quay) and in other official jobs.

Many women worked across the county as domestic servants (see Johanna Cleary at Custom House Quay), as milliners (see Louie McSharry at Parade Quay), as maids (see servants in de la Poer household at Gurteen ) and as dressmakers (see Alice Skeffington at Merchant’s Quay).

Many of those who came for work stayed in the lodging houses of the city (see Mary Kennedy’s lodging house at Arundel), while others found work in the many hotels around Waterford (see Beazley’s Hotel on the Mall). Not everyone prospered, of course. Much work was casual and poorly paid, leaving many unemployed (see Patrick Coad at Francis St.) and others in thrall to pawnbrokers (see Boyce’s of Michael St.).

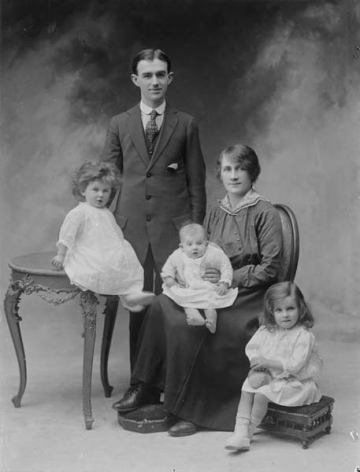

The Fennell family of 21 Mayors Walk, photographed on 14 April 1919. In 1911, the Fennell home was home to Thomas Walsh, a baker, and his large family

(NLI, P WP 2812)

Nonetheless, the economy of Waterford was boosted by its port. Ports bring a particular dynamic to cities. This was particularly the case in Waterford where the port was large and the city small. The men employed around the port carried on a wide range of different trades, often passed from one generation to the next, including ship’s carpentry (see James Long at Salvation Lane). Ships brought in goods from across the world, and on the night that the census was taken in 1911, various nationalities could be found moored along the quays in Waterford, though by far the most common were British (see Benjamin Bennett, moored at Scotch Quay).

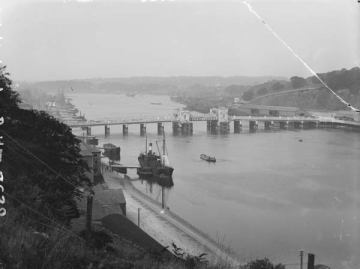

A boat passed through the bridge into Waterford. The port was key to the economic development of the City

(NLI, LROY 11432)

Steamers (see Maunsell Bowers, Superintendent of the Waterford Steamship Company) ran regularly across the Irish Sea from Waterford to Liverpool. They carried cargo in both directions, and were critical to the live export trade in cattle, sheep and pigs, and in the export of dairy produce. In 1917 the Waterford steamers, ‘Coningbeg’ and ‘Formby’ were sunk by German submarines, with all those on board lost. Most of the 83 lost were Waterford men, and included the captain of the ‘Coningbeg’, Joseph Lumley (see his family return for Newtown Rd.).

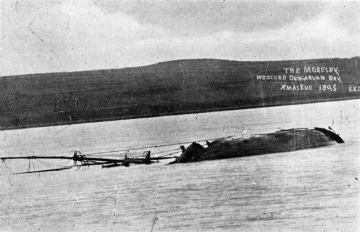

Shipping disasters were not new to the area. In December 1895 a ship called ‘The Moresby’ left Cardiff bound for South America with a cargo of coal. The ship ran into poor weather and, when trying to shelter in Dungarvan Bay, its anchor broke and the ship went on its side. The volunteers of the Ballinacourty lifeboat went to the rescue, but 20 of the 25 people on board were drowned. These included the captain, his wife and their two year old daughter.