What was Waterford like in the early 20th century?

View the photo galleryWaterford in 1911 was an agricultural county, which had as its main urban centre a busy port. This was a county of considerable poverty where thousands of people lived on the margins, and there were evictions of families from their homes. There was also, of course, considerable wealth in the county. That wealth resided with the landed gentry who retained a significant presence in the county, and with the families who owned large commercial operations, usually in Waterford city.

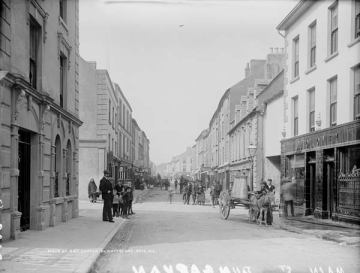

In 1911 only two places in the county of Waterford had a population of more than 2,000 people: Waterford city and Dungarvan. Waterford city had a population of 27,464, and Dungarvan had a population of 4,977. This represented increases of 2.6% in each of the areas since the previous census in 1901. This rise in population in the two significant urban centres was in contrast to a general decline of 3.7% across the county as a whole.

A busy Main Street in Dungarvan ca. 1900. Waterford City and Dungarvan were the only two places in the county with a population in excess of 2,000 in 1911

(NLI, LROY 06602)

Rural Waterford was predominantly given over to pasture, with increasing numbers of cattle and pigs being kept by local farmers. This pattern was one familiar to most Irish counties, and confirmed the ongoing decline of the numbers employed on the land and, in particular, undermined the position of those seeking work as agricultural labourers.

The consequence of this process was emigration. Like much of rural Ireland, the countryside was losing the children of farming families, most of whom were emigrating to Britain and America in search of a living. In the decade before 1911 the numbers who emigrated from Waterford reached 7,000.

This was down on previous decades, but in the sixty years that had passed since 1851 almost 110,000 Waterford people had emigrated.

Some of those who emigrated left directly on the steamers which sailed from Waterford port to Glasgow, Liverpool and London. Along with the ports of Dublin, Belfast and Cork, Waterford had developed as a key point of communications with Britain. The port was the focal point of the city and sat at the estuary of the River Suir in a sheltered bay. The River Suir itself was also navigable by barge, and commercial traffic passed on the 7km of the river which led from Waterford port up to the commercial town of Clonmel in Co. Tipperary.

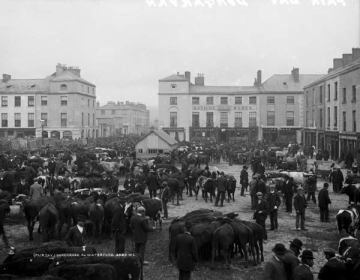

The port of Waterford was vital to the economic development of the city. There was a significant trade in the export of live cattle and sheep, usually to England. There were large-scale fisheries in the area, as well as salt-houses, breweries and flour mills. The sea offered other commercial opportunities: from Waterford Harbour, down past Tramore Bay and Dungarvan Harbour, and south to Youghal Harbour which separates Waterford from Cork, the coastline of Waterford offered stunning scenery to the increasing number of tourists who came to the county in the second half of the nineteenth century.

A tourist retreat: Enjoying a stroll on the beach at Tramore, Co. Waterford ca. 1900

(NLI, LROY 00092)

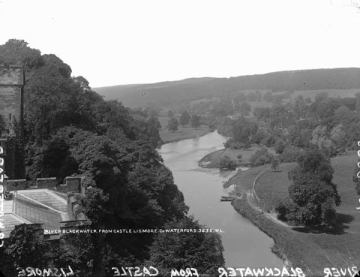

The increase in tourism was due, in no small part, to the fact that Waterford was well-connected by rail. It was connected by line to Dublin and to the north-west of the country, and it was also linked by the busy rail line between Cork and Rosslare in Wexford. The rail link out to Tramore, along the Waterford coast, was developed especially with tourism in mind. It resulted in Tramore developing as the key centre of tourism in the county, with its seaside attractions, racecourse, golf course and hotels. Some came to fish in the sea, while others fished along the River Blackwater which was renowned for its salmon.

Despite its busy port, Waterford was a predominantly rural county. This photograph shows the River Blackwater wending through the Waterford countryside at Lismore ca. 1900

(NLI, LROY 03636)

Politics of Waterford were nationalist, though not uniformly so. There was a significant landed gentry led by the Marquis of Waterford, and the Kings of England had long retained an interest in the city. Henry II had landed near there in 1172 and Richard II did the same on several occasions in the 1390s. In July 1690, it was from Waterford that James II had embarked for France after defeat at the Battle of the Boyne. In 1904, the royal visit to the city of Waterford drew out large crowds who watched King Edward VII proceed through streets bedecked with flags and bunting. The physical heritage of centuries of royal involvement in Waterford was visible in the principal buildings of the city, not least Reginald’s Tower. King John had stayed there in 1210 and the tower took on the functions of a royal palace.

Despite the pageantry of the royal visit, the pre-eminent political figure in Waterford in 1911was John Redmond. Redmond had served as MP for Waterford city since 1891. He had been leader of the Irish Party in the House of Commons since 1900. In 1911 he was moving towards the prospect of remarkable political success. A constitutional crisis in Britain and a dramatic shift in the balance of political power had been adroitly negotiated by Redmond. Home Rule for Ireland was back on the political agenda as a realistic proposition. The following year – 1912 – saw the introduction of the 3rd Home Rule Bill, and Redmond was at the height of his political power, seemingly set to succeed where Charles Stewart Parnell had failed. Ultimately, Redmond failed too, however, undermined by loyalist opposition in the north, by the outbreak of World War 1, and by the shift in nationalist politics in Ireland which resulted from the 1916 Rising. He died in 1917, his dreams unfulfilled, though his son, William, was later elected both an MP and a TD for the city of Waterford.

John Redmond MP, the pre-eminent political figure in Waterford, addresses a large public meeting in 1912

(NLI, IND H 0005)

While Waterford was largely nationalist, it was also largely Catholic, with the census returning the number of Catholics in the county at some 95.7% of the total population. Of the remainder, 3.6% was Protestant, 0.3% was Presbyterian and 0.2% was Methodist. The city of Waterford was slightly more diverse, with the percentage of Catholics falling to 92.3%. Amongst the remainder were Quakers, and 33 people who refused to answer the question on religion in the census form.

The exterior of the Roman Catholic Church at Cappoquin ca. 1900. Over 95% of the population of Waterford was Catholic in 1911.

(NLI, LROY 10014)

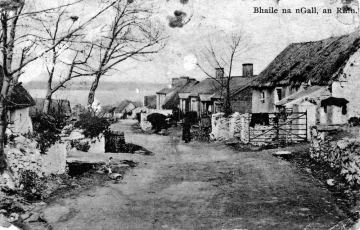

Others filled the census form out in Irish. Indeed, the majority of the returns from the Ring area, which was situated on the southern shore of Dungarvan Bay, were filled out in Irish. This area was unique along the east coast of Ireland. The general collapse in the numbers of people across the country speaking Irish in the second half of the nineteenth century left concentrations of Irish speakers in Gaeltacht areas, along the west coast of Ireland. The exception to this was the Ring Gaeltacht in Waterford. The 1911 census indicated that 23,820 people in Waterford (28.4% of the total population in the county) could speak Irish. Of these, 152 could speak only Irish, with the remainder speaking both English and Irish.